Posted on:

My father spent many years researching his Cameron Ancestry. In the days before the internet this meant studying documents in churches, schools and official buildings. Most of what he found is fact but there were some gaps that he tried to fill with speculation.

Notes

My father struggled to fill the story around the time of Culloden 1946. I guess our embattled Highlanders weren't too keen on filling in forms! Below is an educated guess after having visited graveyards, churches and schools in the area. Where names or facts can not be justified, they are in BOLD ITALICS

From my father:

The imagination takes fire at the thought of one’s ancestors being caught up in a dramatic period of history. This story is partly of the imagination. Some of the characters you will recognize, for they are included in the present research, and their lives are described as the evidence suggests. The history of others of our family, particularly the earlier ones, cannot be justified on the basis of known facts. They are included to make up a cohesive and complete story – a short novel, if you like – just for the fun of it. But the historical background is true.

The Story of a Highland Family (our Cameron Story)

In the year 896 the death occurred of Sitric Halfdansson. His life, at this distance of some 1100 years, is something of a mystery, but there does seem to be a hint of Scandinavia in his name. He was succeded by his son Ranald who was styled ‘King of Waterford and Dublin’. Thereafter the names begin to change from the Nordic sound to the Gaelic, and include, around 1100, Somhairle Mor Macgillebride, King of Argyll, 1st Lord of the Isles, who married Ragnhilda, Princess of the Isles. In 1272 we hear the name MacDonald for the first time, Angus Og MacDonald, son of Angus Mhor MacDonell. Around 1390 the name Shomhairle Ruaidh (Somerled) appears. Four generations later we have Donald McAlister MacSorley-Cameron, styled ‘1st of Glen Nevis’. (Sorlie or Sorley being a translation of the Gaelic Shomhairle or Somerled.) The MacSorlies are thus descended from the same stock as the MacDonalds. During the 13th and 14th centuries, the most important tribes in Lochaber were the Clan Donald, the Clan Chattan, and the Mael-anfhaidh. The latter consisted of three main tribes; the MacMartins of Letterfinlay; the MacGillonies (Mac ghille-anfhaidh); and the MacSorlies of Glennevis (Sliochd Shoirle Riaidh).

The Camerons descended from what looks decidedly like Norman stock, de Cambrun. The 14th Century appears to have been a good one for the Camerons, who were numerous in Lochaber at that time. A number of other tribes adopted the name of Cameron, either voluntarily or under duress, and although the MacSorlies were of MacDonald descent they were ‘encouraged’ to call themselves Camerons. The MacSorlie-Camerons of Glen Nevis were involved heavily with members of the Erracht faction of the Cameron Clan during the murderous stuggle in 1613, when many of the leading members of both were killed by the Lochiel Camerons. It is speculated that around this time a woman of Erracht married a MacSolie-Cameron.

John Cameron of Erracht was born around 1660 and married his first wife Finvola (or Jean) Cameron about 1682. Finvola was the daughter of Donald ‘na Cuire’ Cameron of Glendessary, tutor of Lochiel (Donald of the Knife !). She bore him five children and died around 1700. The first child, a son, died at school in 1693. The second, Donald, married Janet Cameron, daughter of John Cameron of Glendessary, in 1715 and was killed at the Battle of Sheriffmuir the same year. The fourth child, John, died about the age of twenty. The fifth child, Isobel, born about 1698, married Charles MacLean of Drimnin, who was killed at Culloden in 1746. However, they had a daughter, Marsali (or Marjory) MacLean who married her cousin Ewen Cameron of Erracht to become the mother of Sir Alan Cameron of Erracht, founder of the 79th Cameron Highlanders and a famous soldier. Alan was born at Erracht House in Glen Loy, which is there to this day.

But it is with the third son that we are concerned here. He was Allan Cameron, born about 1687 and died the year before Culloden, 1745. He had married Margaret Cameron about 1709. She was the daughter of Allan, son of Donald ‘na Cuire’ Cameron of Glendessary, and therefore a cousin to her husband. She bore him four sons, the first of whom was Ewen Cameron of Erracht, mentioned in the previous paragraph). The second son was Allan Cameron, born about 1712. He married Isobel, daughter of Dugald Cameron of Invermallie about 1740. They lived in Kilmonivaig, just across the River Lochy from Glen Loy.

When Prince Charles Edward Stuart landed on Scotland’s shores on 25th July 1745, Donald Cameron of Lochiel hastened to confer with the Prince, to dissuade him from continuing with the Rising. Donald’s nature and upbringing would not allow him to let down one to whom he had sworn loyalty, and when the Prince insisted that he would continue even though few joined him, he reluctantly agreed to join the Rising. With the prestigious Camerons on board, other clans soon agreed to join them, and the die was cast.

Allan answered the call from his Chief, and went away to war. On 20th September he was in the victorious Highland army at the Battle of Prestonpans, and he and 650 Camerons marched into England on 1st November. By 26th December he was in Glasgow, following the retreat from Derby. Two victories followed, on 8th January at Stirling and 17th January at Falkirk. The retreat to Inverness began at the end of January, and the Highland Army was finally destroyed at Culloden on 16th April 1746.*

Allan made his way down the eastern side of the Great Glen, and arrived home wounded and exhausted to find Isobel distraught with worry. Allan had stories to tell of the ferocity of the Hanoverian troops as they rooted out suspected Jacobites from their homes and shot them out of hand. They agreed that they must leave everything but necessities, and make their way over Rannoch Moor, where many of the survivors were headed. They would be safer in Rannoch than anywhere else. It was remote,and the terrain difficult to cross, and where the hills would afford fugitives a good view of the Moor, and anyone approaching.

The months following were a nightmare of fear and hunger. They reached Loch Rannoch, and joined a number of other refugees. A barracks containing a detachment of the Duke of Cumberland’s troops appeared, and created a barracks at the Braes of Rannoch, so Allan and the other men took to the hills where the troops would not venture. They sustained themselves by ranging far and wide to steal cattle, and by so doing helped to create the reputation of Rannoch as being a place of thieves and murderers.

*But they survived, and gradually a number of enlightened officers began to establish civilised society, building houses and schools, and encouraging teachers and tradesmen to come into the area.

***Allan returned to the home they had established on the northern shore of the loch at Killiechonan, and they worked hard to make the land fit to produce crops. They also had a son,***Duncan, born in 1753.

At the age of six Duncan went to the little school in the hamlet where they lived at Killiechonan, and as he grew to be a strong youth he helped his father on the land. In 1775, when he was 22, his father at 63 could no longer cope with the hard work on the land. The privations he had suffered had aged him before his time. Isobel died in 1780 at the age of 58, and Duncan looked after his devastated father for many years. In 1792 Allan died at the age of 80, and Duncan decided that it was time, at 39, to go and get himself a wife.

He had met a girl some years previously, Grizal Kennedy, who lived with her family in Fortingall, about fifteen miles away. They married in 1792 when he was 39 and she 22.They decided to look for a home away from Rannoch, and travelled south to Callander. Their son John was born after a decent interval at the home they made at thelittle hamlet of Ruskie*, *near the village of Port of Menteith, a few miles from Callander, on the shore of a little loch.***They had a plot of land, and Duncan, with his experience of farming, set out to keep his family well fed and housed. He was successful working the land in this much more fertile area, and as John grew up he took over some of the hard work from his father. But farming was not John’s idea of a lifetime occupation. He was ambitious to learn a skill that would give him security to have a wife and children of his own, and determined to seek his fortune in a big city where there was excitement that was lacking in his life in this backwater of Perthshire. ***

With the blessing of his parents, he set out for Glasgow in 1814 at the age of 19. His father was 61 years old, and his mother 44, but he was satisfied that they would manage to live off the land, which he had left in a good state.

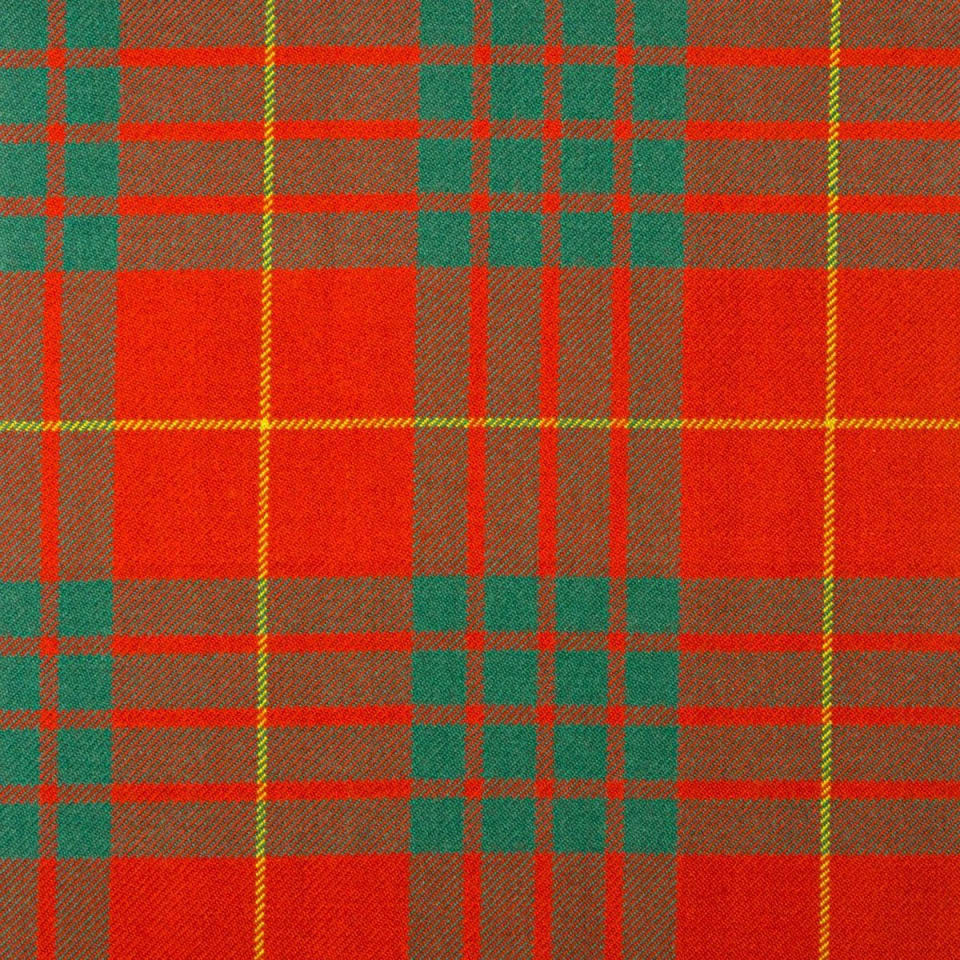

In Glasgow he soon found his feet, and got a job in a mill to give him some income to live on. Meanwhile he looked around for a good-paying trade, and finally settled on weaving. Weavers were the elite of the working class, and the centre of the weaving trade was Paisley. His attitude to learning the craft was impressive, and he soon became apprenticed to a weaver in Paisley. By the age of 25 he had learned a great deal of the skills required to become a cottage weaver, and departed to find work in the small weaving town of Kilbarchan, a few miles south-west of Paisley.

He was an enterprising young man, and soon joined a co-operative where looms were jointly owned, and the participants shared the jobs of preparing the spindles of thread, setting up the looms, and producing the cloth*. *He was also a personable young man, and soon found his soul-mate in a young girl living in the town with her parents. Her name was Janet Mitchell, and her father was a weaver. John, seeing both a wife and a business start-up, fell in love. His feelings were reciprocated, and in no time at all they were ‘going out’. Everything had to be very ‘proper’ in this deeply religious town, and the proprieties were observed. James Mitchell gave John good advice on both weaving and the art of being a good husband, and Martha Mitchell made him the recipient of many of her pies and pasties.

John and Janet were married on 7th December 1821 at the kirk in Kilbarchan, a town which John was to make his home for the rest of his life. They obtained a weaver’s cottage at 12 Shuttle Street, and settled down to put to good use John’s skills as a weaver, aided by his adoring Janet.

Janet proved to be a wonderful wife, mother, and, in the intervals between babies, apprentice weaver. She presented John over the next twenty years with seven children, all healthy specimens, and all eventually married except one. The exception was Janet’s last baby, Duncan, born in 1842. He turned out to be every bit as ambitious as his father, and went away to study to be an engineer. He was successful, but before he could put his skills at the disposal of a wife, he died at the age of 26. The cause was phthisis, which he had suffered for two years, a disease of wasting of the lung, probably due to pollution in the atmosphere from industrial waste. The next generation were to suffer badly from the same disease.

As soon as each child was old enough he or she became apprenticed to their father. The youngest child, Duncan, mentioned above, was born in February 1841, and they all lived in a small weaver’s cottage in the (appropriately named) Shuttle Street. In June of that year there were nine of them. The working area, where John worked and where the children prepared the spindles and the loom, was in a lower room, and the living quarters consisted of two rooms on the ground floor of the cottage. They were not lucky enough to have one of the larger cottages, with a further two rooms on an upper floor*.* The beds were recessed into the walls and, of course, they had to ‘double up’.There were sash-type windows in the two living rooms.

The third child of John and Janet, born in 1828, was John, named after his father.He was to be the one to carry on the line to ourselves.

In 1845 John’s father Duncan, now on his own after losing Grizal the previous year, made the painful journey from Port of Menteith to Kilbarchan. He was 92 years old, and John took time off to escort him to his final home. He died seven years later, having just missed his century.

Between 1849 and 1858 the five daughters, Grace, Martha, Jean**,** Janet and Mary, all married. John (son) remained at home, by the age of twenty a skilled weaver himself. He met young Elizabeth Murphy, an Irish girl of his own age, in the town and they fell in love. She was in service with the family of a well-to-do merchant. They married in April 1852 and found a cottage in Church Street. Now John and Janet were on their own for the first time in over thirty years. John was 57 and Janet 54. Their solitude was not to last, however. Mary lost her much older husband Hugh McKeith in 1857, and Janet lost her husband John Robertson in 1860. Both Mary and Janet returned to the family home, and they all moved to Cartside, near to the river Cart, which flows to the east of the town, in 1865. Janet died in November 1872 at the age of 74, and John followed her four and a half years later, in 1877 aged 85.

Meanwhile John and Elizabeth were blessed with their first child in 1853, a little girl Janet, named after the mothers of both of the happy parents. Young John arrived in 1855, followed by Ann in 1856, Robert in 1858, Peter in 1860 and Duncan in 1862. Then came years of tragedy.

Towards the end of February 1863 Peter aged 2 contracted gastric fever and died in March. The following month John, the second-born, who had suffered from mesenterica disease since he was about five years old, died before his ninth birthday. The month after that, little Duncan, only five months old, died of bronchitis and pneumonia after an illness of 16 days.

Another daughter, Grace, was born in 1864, but tragedy was to strike two years later when the first-born, Janet, died at the age of 13, two months before another son was born. They called this new baby John in memory of the first John who had died three years before, but at 10 months the little chap was convulsed for four weeks with whooping cough, and died in March 1867.

The following January (1868) Thomas was added to the now greatly-diminished family, and Duncan in February 1870 (Duncan was to be the progenitor of the Hartleys and the Camerons in England.).

Fate, however, had not finished with this family. A new daughter,Elizabeth, was born in 1872 but died of phthisis after a fifteen month illness at the age of four. Shortly after her death, another Elizabeth was born, in November 1876. She was to be the last child of John and Elizabeth.

There were two further twists of the knife in the hearts of the parents. Thomas had reached 12 when he died of abdominal phthisis after an eight-month illness. There was a long interval before the final blow when, in 1894 Elizabeth, now 17, died of tuberculosis in Paisley.

Of the twelve children born to John and Elizabeth, only four reached maturity: Ann, Robert, Grace and Duncan. Grace never married, and died aged 74 in 1939 at Paisley Infirmary. Robert married Ann Inglis and left Kilbarchan. Duncan met Margaret McCrone Ferguson, who lived in nearby Johnstone. She became pregnant, and they married at Johnstone on 25th December 1897. Their daughter was born 2nd March 1989 in the same town. She, like her mother, was given a second Christian name to perpetuate the surname of her maternal grandmother – Janet McQuilton Cameron. A son was born on 22nd April 1900, John Cameron. Some time after that the family moved to Leeds in England, and Duncan took a job as a travelling salesman for a paper manufacturer, which he retained until he retired. He was well-respected, and a loyal member of the bowling club at Headingley. He died aged 63 after a series of leg amputations, due to gangrene picked up, it was thought, on the beach at Bridlington. Margaret died five years later, aged 65. Both are buried in Lawnswood Cemetery, Leeds.

Duncan and Margaret took a small terrace house, 16 Newport View, near Headingley cricket and rugby ground. Next door to them lived a family with four sons, the Hartleys. The second and third sons were in the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry during the First World War, and both were wounded at the Battle of Loos in 1916. The third son, David Lincoln Hartley, never really recovered from his wound and died about 1928 after having married and fathering a posthumous son, also David Lincoln, who died early in infancy. Janet had her eye on the second son, Maurice, and they eventually married in 1922. After a still-born son in 1924, in 1926 they had a son, John Duncan, named after both his grandfathers. Janet’s brother John married Constance Alice Taylor (Connie), born in Kenilworth in 1899, and in 1941 they produced a son Ian Kenneth Duncan.

Janet and Maurice had only the one surviving child, John Duncan (usually just called Duncan), who joined the Royal Navy at 17 when the Second World War was in its fourth year. Before joining the Navy he had met Margaret Leak, and several years after demobilisation they married. Margaret had been born in Canada of British parents, but had been in the England since she was five. They had three sons, Richard (1955), Michael (1959) and David (1961). Maurice suffered from painful arthritis for almost twenty years until his death in 1967. Janet carried on as a widow for the next seventeen years, but died of cancer in 1980 after a short illness. Margaret died at the end of 1997, losing a brave fight against cancer for seven years. Duncan died on 27th December 2020 aged 94.

Tagged with:

More posts: