Notes:

- Harry's own writings are shown in italics

- All maps expand on click to allow scrolling of features

- External links open in new tab except for Maps and Geolocation References

Introduction

Horace (Harry) Leak was our grandfather. During his life he didn’t talk much about his experiences during World War One. Old soldiers seem reluctant to do so. I guess the horrors of those times tend to be bottled up within. During his latter years, maybe thinking unconsciously about the need to pass on his stories, he did open up a bit to my two brothers and I. He also left us with a mass of written notes about his war time years, which make for fascinating reading.

We have analysed these notes as best we can and tried to date and validate them. To assist us we have read published books about his units, firstly the 1st 7th Battalion (1917) and secondly the 1st 5th Battalion 1(1918) of the 49th West Yorkshire Regiment. In addition we have the advances of the internet to thank, for example, detailed trench maps and the Battalion War Diaries. These provide an invaluable resource and have helped pull together his notes.

There is a certain consistency with all of Harry’s 200+ pages of war memories. Yes, there are many repetitions, but plenty of consistencies too about those events. That very consistency gives a certain authenticity to his story. Certain of his recollections have been found to be incorrectly dated, I guess an 80+ year war veteran can be forgiven for getting some of these wrong. The Battalion War Diaries at least gave us a chance to verify all his dates.

I have not tried to re-write Harry’s notes within this story, neither correct nor put into "better English", apart from the odd spelling change or to apply better punctuation. The quotes I have used have been replicated here in his own inimitable style. For those fortunate enough to have known him, they will instantly recognise his words.

He was just an ordinary guy. No swashbuckling hero, no testosterone filled muscleman, just an ordinary "Tommy" doing his bit for his country. He was a larger than life character though, always smiling, singing and laughing, a gentle soul as these war notes reveal. During the war years it seems he never lost his humour, empathy nor humanity. And … that is some feat.

The following is a story of his war.

WWI References

- The West Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War, 1914-1918 Volume II by Everard Wyrall 1927

- Harrogate Terriers 1/5th (Territorial) Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment in the Great War by John Sheenan

- Passchendaele – the story of the Third Battle of Ypres 1917 by Lyn Macdonald

- The West Riding Territorials in the Great War by Laurie Magnus

- British First World War Trench Maps, 1915-1918 - National Library of Scotland

- Trench Maps and Aerial Photographs | McMaster University Library

- Great War Forum

- British Army war diaries 1914-1922 - The National Archives

Official War Record

- Date of birth: 9th September 1895

- Service Number: 23904

- Regiment: West Yorkshire Regiment

- Battalion: 1/7th and 1/5th Battalions

- Rank: Private

- Campaign Medals: Victory Medal, British Medal

- Wartime Chronology: Enlisted 20 November 1915 (approved 21 January 1916)

- Known Movements/Incidents:

- Zonnebeke Gasometer

- Stationed at Cologne at end of war

- Discharged on 21st September 1919

Lyn Macdonald

Within Harry’s handwritten notes there are numerous copy letters to a "Lyn Macdonald". She has written many World War One historical books mainly reliant on recollections from old soldiers, such as Harry.

Since leaving her job as a BBC Radio producer in 1973, Lyn Macdonald has established an unrivalled reputation as an author and historian of World War I.

She has produced six volumes of superb popular history, remarkable for their extensive use of eyewitness accounts. She is the recording angel of the common soldier. "My intention," she says, "has been to tune in to the heartbeat of the experience of the people who lived through it." Besides drawing on the oceans of contemporary letters and diaries, she has captured the memories of a dwindling supply of veterans.

We have two of her books to see whether any of Harry’s memories are replicated but sadly, he is not mentioned. Nevertheless these are superb historial works and should be read by all who have interest in World War One.

"They Called it Passchendaele: The Story of the Battle of Ypres and of the Men Who Fought in it. 1917"

"The Roses of No Man's Land"

Harry’s thoughts on the war up to enlistment in late 1915

Now when war was declared on 4th August 1914 I must admit that England had the most powerful navy in the world, but our army stretched all over the world, wherever there were British interests.

We had reserves in both navy and army and they all soon answered the call and so did all the colonies, Anzacs, Aussies and Canucks. Just to be sacrificed, as right up to the end of 1917 our Chiefs of Staff thought the war could be won with the bayonet.

Great Britain got caught with their pants down to put it bluntly. Take Gallipoli, the Somme, Ypres. No wonder Flanders was to stem the tide of the German advance.

I guess also in the first year our artillery was not getting enough shells for the guns. So they were limited to using them only when really necessary. So this is one thing, if we had had lots of machine guns or Lewis guns the average Tommy would have been a lot happier.

Enlistment

Harry and some of his pals had tried to sign up to fight for king and country earlier, but it wasn’t until late 1915 that he was called up. He was just 20 years of age. He enlisted on 20th November 1915 and that enlistment was approved on 21st January 1916, so he joined the 1st 5th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment 49th Division.

In 1914 and 1915 you had to be fit and in perfect health to join the army. In 1914 my two pals and I tried numerous times to get in the army. One recruiting officer made the remark, we sure would be useful if only as pull-throughs. We were skinny runts you see. We tried various places and the usual skits were thrown at us, like ‘Go Home and Eat a Cow between two slices of bread!. It was only late in 1915 that we got the ‘King's Shilling’ to be called up at 24 hours notice.

Note: The expression ‘to take the king’s shilling’, meant to sign up to join the armed forces. Rather like with the ‘pressed’ money for the ‘impressed’ man, a bonus payment of a shilling was offered to tempt lowly paid workers to leave their trade. Once the shilling had been accepted, it was almost impossible to leave.

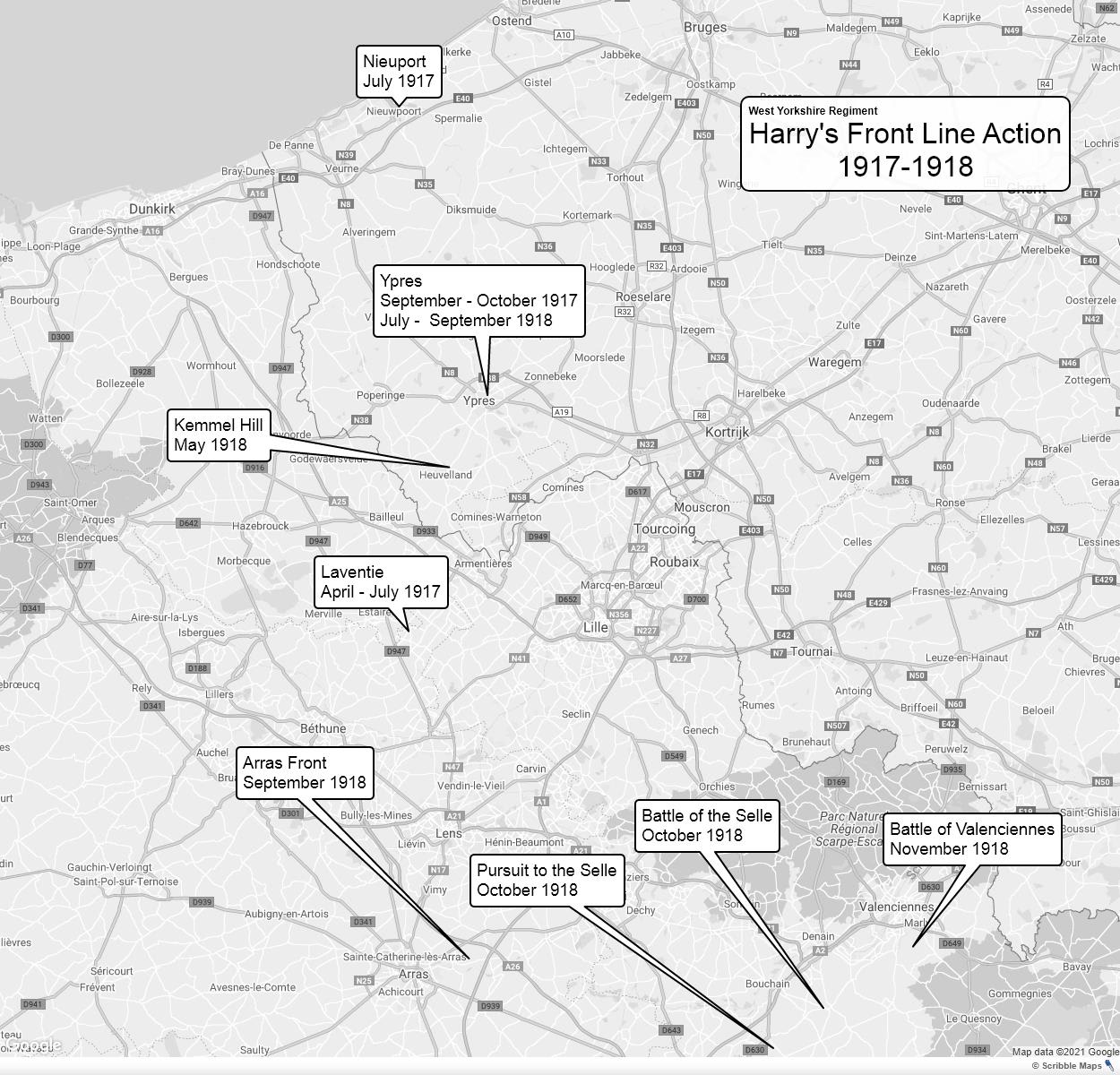

The Regiment was first mobilised for war in April 1914 and saw action in May 1915 at the Battle of Aubers Ridge and in December against the first phosgene gas attack. 1916 saw further battle honours at the Somme i.e in the Battle of Albert, Battle of Bazentin Ridge, Battle of Pozieres Ridge and Battle of Flers-Courcelette. image11.jpg" "Map: Wartime Front Line Action" %}

An initial three months of cold, hard training took place primarily in the Redcar and Newcastle area, followed by heading into Northumberland for intensive training and the rifle range.

We were sent to Redcar where we were inoculated in one arm and vaccinated in the other. I think he must have been a veterinary doctor because the very next day he came and wanted to look at out feet. He told me my feet were perfect, I had a high instep. It was all Dutch to me.

In Newcastle we were billeted in a roller skating rink in St Mary’s Place off Northumberland Road. For the next three months we had hard training all day long on the town moors. It was very cold and we sure enjoyed the hot meals waiting for us afterwards.

Mediterranean Bound

After the initial training in the North-East, rather surprisingly, he was issued with tropical gear and put on a train heading south. On 6th May 1916 his battalion boarded the ship Ivernia out of Devonport. 2000 raw recruits were packed into the holds of the ship which had a stormy passage through the Bay of Biscay before arriving in Gibraltar for a brief stop over to take on provisions.

We had a rough passage in the Bay of Biscay and I did not eat anything as I had the misfortune to only have 1 penny in my pocket. Not enough to buy an apple. I wished I was back in the brickyard earning a decent wage.

At this point they were still unaware of their final destination. They had feared they were bound for Gallipoli and the Dardanelles, so were quite happy when they pulled into Valletta, Malta.

After leaving Gibraltar we went up the Mediterranean. We began to feel a little anxious as rumours were going around we were going to the Dardanelles. Anyway they were all wrong, a few days later we dropped anchor in the Grand Harbour in Malta.

Fortunately for Harry he was one of the sixty or so that were picked out to stay in Malta and unload hospital ships, helping the existing half a battalion of old Boer War veterans with this important work. Lots of sick and wounded came in there from Gallipoli and Salonika.

Well we were very fortunate to be there and we’re kept very busy, but in a way we were very glad as we were not at Gallipoli.

The first month was spent in Floriana Barracks until the necessity for beds for the sick and wounded meant they were moved into tented accommodation. This site was on an old burial ground that sloped down to the harbour which was very convenient for "out of work" bathing time in the hot weather.

One day my mate and I went down to the harbour and spent the day swimming down there. This wasn’t allowed unfortunately. We got back at 6pm. During the night we both had to be taken to the hospital as we were delirious. The doctor said we had "Sand Fly" fever. We were in the hospital for about three weeks. For the next two weeks we had no solid food, just slop. And, that is why I don’t like milk puddings, even as of today. We were glad to get back to the barracks, until the CO put us on a charge and then gave us three weeks confined to barracks with no pay!

There is one thing we get very good meals and we sure enjoyed them as we were on a shilling a day payment and I had made an allowance to Mum of 3/6 a week. I think they made up to 5 shillings a week for my mother.

His building skills were put to good use, even in those days.

One day they held a competition for the tidiest marquee. Me and my mate Jimmy Grass went for it. We collected all the large rocks from the hillside around and made surrounding walls that kept the goats out. Then we levelled off the floor using soil from the cemetery and mixed it with water. In the high temperatures it set as hard as concrete. We shared the money around the marquee.

Harry seems to have been a "bit of a lad"!

I was on guard duty at the Main Guard room in Floriana Square opposite the Governor's Palace and there was a band playing every afternoon. Well the rule was you were allowed to stand at ease and when I stood like that one time I was kind of doing a tap dance with one foot. Little did I know I was spotted by someone in the Palace. I think it was the Governor's son. That resulted in four days confined to barracks.

He suggests that he had a girlfriend back in England.

In July I had a letter from the mother of the girl I was courting to say she was ‘walking out’ with the Foreman where she worked at the Paper Mill. In fact I knew him, he went to the same school as I did. So in a way I did not bear anyone a grudge as it was well known that I never intended getting married whilst the war was on. It left me rather relieved.

There were interesting other duties Harry had to perform.

In November six of us were on duty at the cold meat store and it rained continuously for twelve hours. The wind was terrific. When we got back to camp the next morning nearly every marquee was flat on the ground. Gee whizz, everyone was busy sorting out belongings and our mates said we was darned lucky to go on guard duty during the storm.

For the next two months two of us were out every other night with a signaller on observation duty on the seafront. If there was a light shining out in the Mediterranean he would fix a telescope and then draw a sketch of it.

All good things come to an end though, especially during wartime. Harry had really enjoyed his time in Malta but in late December they received notice that they would be shortly heading for the continent.

There was a daily paper printed in Malta and it was very gloomy about the future, both in the east and the western front. It didn’t alter the fact that there were still terrific casualties always arriving. In February we were refitted and were guessing where we would be bound for. We soon knew it was for France and Belgium.

Off to War

In January 1917 they boarded a ship in Valletta harbour bound for Marseilles in France. There they were put into box cars on a freight train which headed north. Harry complained about the meals!

I remember we were all quite excited when the Sergeant told us we were going to have Pork and Beans. What a surprise, a piece of greasy pork on top of a tin of beans. One look at that was enough. It was terrible, it felt like we were going from the sublime to the ridiculous. As far as that and porridge was concerned, I would never sample again.

It must have been four difficult days before they arrived at their destination, Étaples, south of Boulogne on the northern coast. This was the principal depot and transit camp for the British Expeditionary Force in France.

On arrival we were all examined by the doctors and declared fit. In a lecture we were told that we would start extensive training.

They put you through the mill alright, galloping around in the soft sand from one trainer to another in heavy soled boots. We were glad to get back to camp at the end of the day.

The camp we were at was as strict as any prison. The Red Caps caused a lot of trouble. There were four sergeant instructors there that took charge of us and they certainly put us through the mill, as the saying goes.

An instructor took a violent dislike to me. I said that the bayonet was no good against the machine gun and during the subsequent bayonet training he gave me a heck of a wallop over the knuckles of my right hand. Right away I swung the butt of my rifle at his chin but sorry to say, I missed. Anyhow I was arrested and put under guard at the camp for Attacking a Warrant Officer.

Next morning the camp commandant told me that it was a serious charge. The instructor said he just gave me a slight tap on the knuckles. I showed the commandant my hand and he blew his top at the instructor. I was let off with a caution, he tore the charge sheet up, excused me of all duties and told me to get my hand seen at the ambulance tent.

We were very glad to leave Etaples.

A few days later in St Omer I was also picked on by a Sergeant and got four days confined to camp. Just about that time they issued us a green envelope. This would be used for family communications only and not be read by the Censor Officer. I wrote to my brother, Harold, who was also serving in a Territorial Regiment. Unfortunately, the Censor Officer saw a green envelope addressed to a H.Leak, written by a H.Leak and became suspicious. He opened it and read the contents which I can assure you were not very complimentary. He told me I could be shot for what I had written. I apologised and said I was sorry. He gave me the letter which I tore up in front of him. You see, the officers that rose from the ranks knew all the tricks of the trade and it was no use trying to pull the wool over their eyes.

The military camp at Étaples had a reputation for harshness and the treatment received by the men there led to the Étaples Mutiny in 1917. Étaples was also, from a later British scientific viewpoint, at the centre of the 1918 flu pandemic. The British virologist, John Oxford, and other researchers, have suggested that the Étaples troop staging camp was at the centre of the 1918 flu pandemic or at least home to a significant precursor virus to it.

They also spent some time in the Dunkirk area to do intensive training in the sand dunes. On training:

Well most of the time on the sands near Dunkirk was bayonet fighting and I thoroughly detested it. Of course the Sergeant Instructor knew that, so he quite naturally picked up on me. He said "Why don’t you curse and swear?" Well you see, I had an awful experience with a most vicious Sergeant Instructor at Etaples after arriving from Malta, so I made sure it was not going to happen again. I put up with it.

Harry found the training tough and they were really put through the mill for the next few weeks. One day they were transported to St Omer for an inspection parade. Here they were told that they were joining the 1st 7th West Yorkshire Regiment.

It sure made me a lot happier as that regiment was the Territorials together with the 1st 8th Battalion of the 49th Division. There were quite a lot of chaps from Leeds and the district there.

A day later they headed for the front line at Fauquissart.

Fauquissart Front, Laventie (April-July 1917)

For several months (from the end of February to the middle of July, 1917) the 49th Division spent a comparatively quiet period in the Laventie area between the towns of Armentieres and Bethune. In a way it was recompense for the long, weary and terribly exhausting months through which the Division had passed, in the Ypres Salient, soon after its arrival in France. Of course, Harry had fortunately avoided all that action in 1916.

The War Diary of the 1/7th West Yorkshire (Lieut.-Colonel C. H. Tetley) up to the date (5th July) when the battalion left the trenches in the Fauquissart sector for the last time, contains few items but the words "nothing to report." To be honest it was a rather quiet introduction to the war front for Harry.

With the exception of small raids and patrol encounters no attacks were made by the enemy or by the 49th in the Fauquissart sector, and yet it is impossible to dismiss those four and a half months of trench warfare without some mention of life there for the1/7th Battalion of West Yorkshiremen comprising the 146th Brigade of the Division. It was overall a relatively gentle introduction to the war.

We were lucky, the Germans were retiring as we were approaching. The trenches there were very strong and also very dry. Duck Boards to walk on too.

On the 11th July the battalion moved from Laventie to billets in Estaires and onwards to the Dunkirk area and the Nieuport front.

**Map: Lavantie Front Line

ssart (right sub-sector). Reserve either at Levantie or Red House #

- April 1917 Front line Fauquissart (right sub-sector). Reserve either at Levantie or Red House

- May 1917 Front line Fauquissart (right sub-sector). 12th - 18th Reserve at La Gorgue.Reserve either at Levantie or Red House

- June 1917 Front line Fauquissart (right sub-sector). Reserve either at Levantie or Red House

- July 1917 1st - 5th Front line Fauquissart (right sub-sector). 6th - 10th Laventie. 11th - 13th Estaires training

St Georges Sector, Nieuport (July 1917)

Harry doesn’t have much to say about the last week of July 1917 when the divisions were posted to the front line at Nieuport, east of Dunkirk. He does mention that he went there but he gives few details. And yet, as the reports below suggest, it was quite a traumatic time, although the brunt of the gas and barrage attacks seem to have been borne by the 1/5th and 1/6th, and outside of the St Georges Sector of the front.

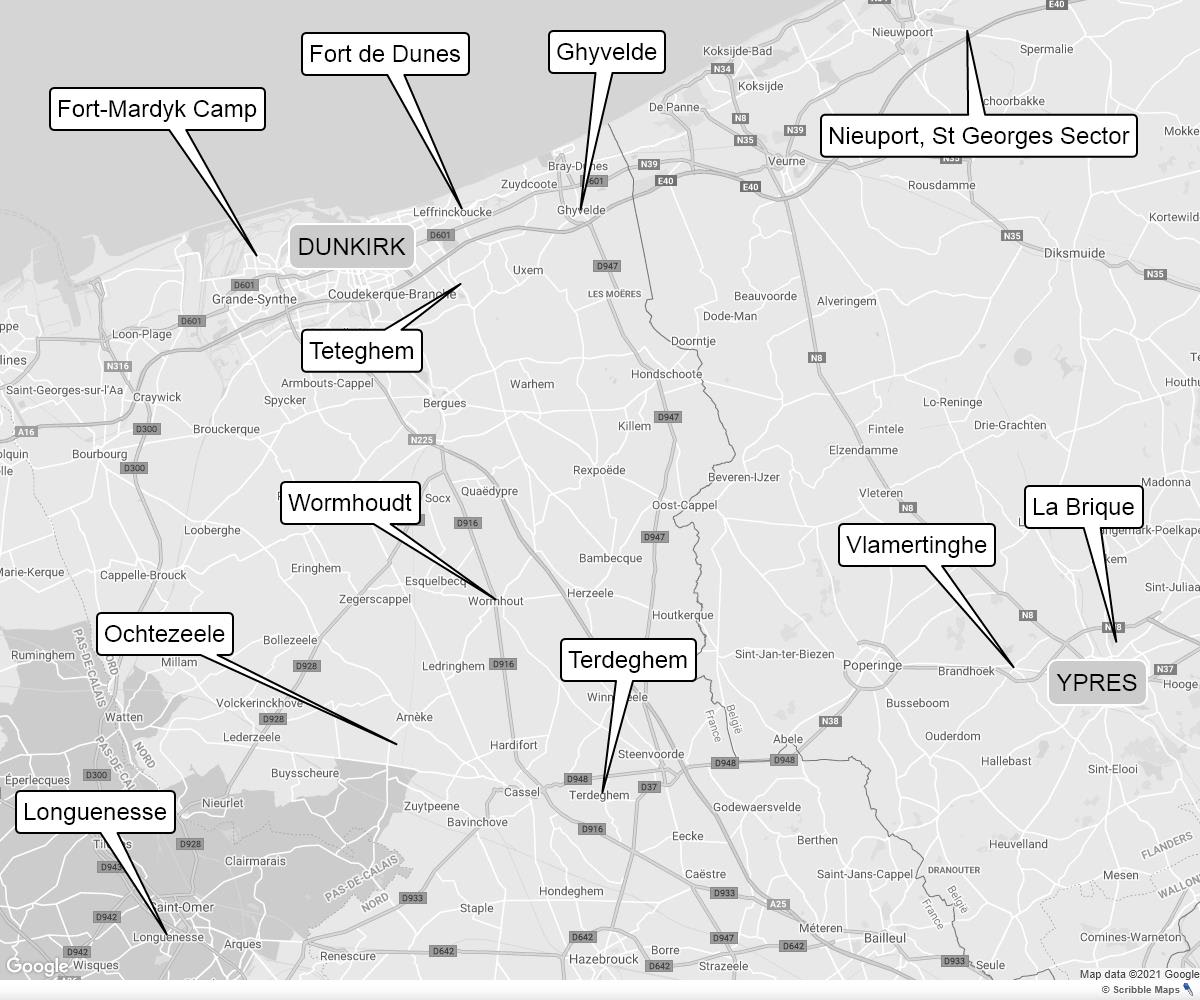

About the middle of July the 49th Division moved to the Belgian coast. The 146th Brigade began training at Estaires for the Fort Mardyck area on 13th, and the move was completed by the 14th, the Brigade being then in camps amongst the sand dunes, south-west of Dunkerque. The Brigade was to have had a week on coast defence, but plans were suddenly changed and on 17th all units moved to the Coxyde-Oost Dunkerque area, under orders to take over the right sector (St. George’s) of the Nieuport trenches. On the 18th the Brigade took over the front line from the 96th Brigade (32nd Division), the 1/6th West Yorkshires relieving the 2nd Inniskillin Fusiliers in the right sub-sector, the 1/5th relieving the 16th Lancashire Fusiliers in the left sub-sector; the 1/8th Battalion went into support billets at Nieuport and the 1/7th to Rebaillet Camp, in reserve.

The new sector is thus described by Capt. E. V. Tempest (1/6th West Yorkshire Regiment):

The Brigade sector was divided by the canalised Yser river, a broad waterway about thirty-five yards wide. Another waterway, the Passchendaele Canal, formed the left of the Brigade front and on the right was Noord Vaart. All these waterways ran into a wide and deep canal which surrounded the town of Nieuport. Thus the communications of the front line depended on bridges.

There was a very great contrast between the right and left sub-sectors of the Brigade front. On the right, in what was called the St. George sector, a reach of water one kilometre in extent, strengthened between our own and the enemy lines. Naturally this sector was very quiet. On the left, the Brigade was holding about 500 yards of the bridge-head on the north of the Yser, which remained in British hands after the July 10th attack. This sub-sector was extremely unpleasant and noisy. It was therefore arranged that the 1/6th Battalion should remain in the St. George sector during the whole time the Brigade was in the line, and that the other battalions should relieve each other every four days in the left sub-sector.

Thus the 1/6th Battalion was extremely fortunate, and our men were able every night to look northwards across the Yser to the lines on the left near the Passchendaele Canal and Lombartzyde, and from their comparatively quiet area regard the incessant fury of a constant battle, rather in the same way that men from Authville Wood in 1916 looked across the valley to the fighting in the Leipzig Salient. No battalion, however, in the Nieuport sector in July could escape heavy casualties, as all roads and trenches converged on to the Nieuport Bridges. And it is no exaggeration to say that every man who lived in or walked through Nieuport from July 18th to July 29th was lucky if he escaped becoming a casualty.

The Brigade Diary comments on the new line thus: "Very little work has been done in the sector — trenches (breastworks) not even bullet-proof — communications very bad indeed." With the exception of violent shelling by both sides and patrol work by night, little happened until the 22nd July, when the enemy vigorously shelled Nieuport and area with gas shells, causing very heavy casualties throughout the whole of the 49th Division.

On 22nd July the bombardment began between 11pm and midnight, the town of Nieuport being literally drenched with gas. The diary of the 1/6th speaks of it as a new kind of gas, and although the battalion suffered less than any unit in the neighbourhood, its total losses were 38 gassed. The St Georges sector was really outside the shelled area but the gas was very insidious.

But this front is significant for it was the first time that a new type of gas had been used. The finest description of that terrible experience is thus given by Capt. Tempest in his History of the 1/6th Battalion:

The gas bombardment of Nieuport was one of the great and terrible experiences of the War. The gas shells came over with a peculiar scream quite unlike ordinary barrage fire and the explosion was slight, merely a sharp ‘ping’ as the glass nose of the shell was broken and the gas poured out. Compared with the earth-shaking crashes of an ordinary bombardment this steady rain of thousands of ‘yellow cross’!!! gas shells seemed ominous, like silent death. Terror took hold of every man as battery after battery of enemy guns poured more and more shells into the thickening gas cloud which lay over the town and all the approaches to the bridges. The gas was so deadly that if a man received the full force of the explosion he was killed instantly. His comrades, not realising that he had been gassed, in some cases delayed a few seconds before putting on their helmets. They could not see the gas fumes in the darkness and the smell was novel, not unpleasant — rather like burnt mustard. But even those few seconds delay were fatal … Before dawn, on the roads and tracks immediately south-west of Nieuport, there were hundreds of men in every stage of the disease, lying down in exhaustion on the roadside. Every few minutes their numbers were increased by small parties of blinded men, one man holding on to the other, often led by a comrade who was coughing his lungs away or could not speak … As often seemed to happen on these mornings of supreme tragedy, the dawn on 22nd July was more than usually beautiful. The red rays of the sun gave a wonderful rose-coloured tint to the gas clouds and smoke which hung over Nieuport. To those standing amongst the gassed men in the fields south of the town the ruins of Nieuport seemed invested with an unforgettable glory. The beauty and horror of the scene seemed inextricably mixed as in an amazing dream. The glories of the rising sun quickly passed. The long line of gassed men groped wearily towards Oost Dunkerque.

For all the days of their lives, from the rising up of the sun to the going down, the survivors of that terrible gas attack shall not forget it; it was one of the most awful experiences through which the 49th Division passed.

The 1/7th were in the Dunkirk area mostly in reserve or supporting the left sub-sector of the St Georges front line trenches at Nieuport. Between the 26th July and 1st August however they were front line troops.

With typical understatement the Diary of the 1/7th Battalion merely records that the "Battalion ‘stood to’ for S.0.S. left Brigade. No developments. Intense bombardment."

Map: Nieuport Front St Georges Sector

Geolocation References

- Geolocation St Georges Front 51.12955, 2.79344

- Google Maps St Georges Front

- What 3 Words St Georges Front

Location Extracts from 1/7th War Diaries

July 1917

- 14th - 16th Mardyk Camp

- 17th Fort de Dunes

- 18th - 26th Ribaillet Camp

- 26th to 31st Front line St Georges (left sub-sector)

August 1917

- 1st Front line St Georges sector (left sub-sector)

- 2nd Oost Dunkerke

- 3rd Ghyvelde

- 4th to 28th Teteghem training in sand dunes

- 29th to 31st Ghyvelde training in sand dunes

September 1917

- 1st to 24th Ghyvelde [Dunkirk]

- 25th Teteghem [Dunkirk]

- 26th Wormhoudt [Nord department in N.France]

- 27th - 28th Ochtezeele [Nord department in N.France]

- 29th - 30th Longuenesse [St Omer]

Map: Approach to Ypres 1-8 October 1917

October 1917

- 1st Longuenesse

- 2nd - 3rd Terdeghem [Steenvoorde]

- 4th - 6th Shrine Camp

- 7th Vlamertinghe

- 8th Bricke

- 9th - 11th Calgary Grange [Battle of Poelcapelle]

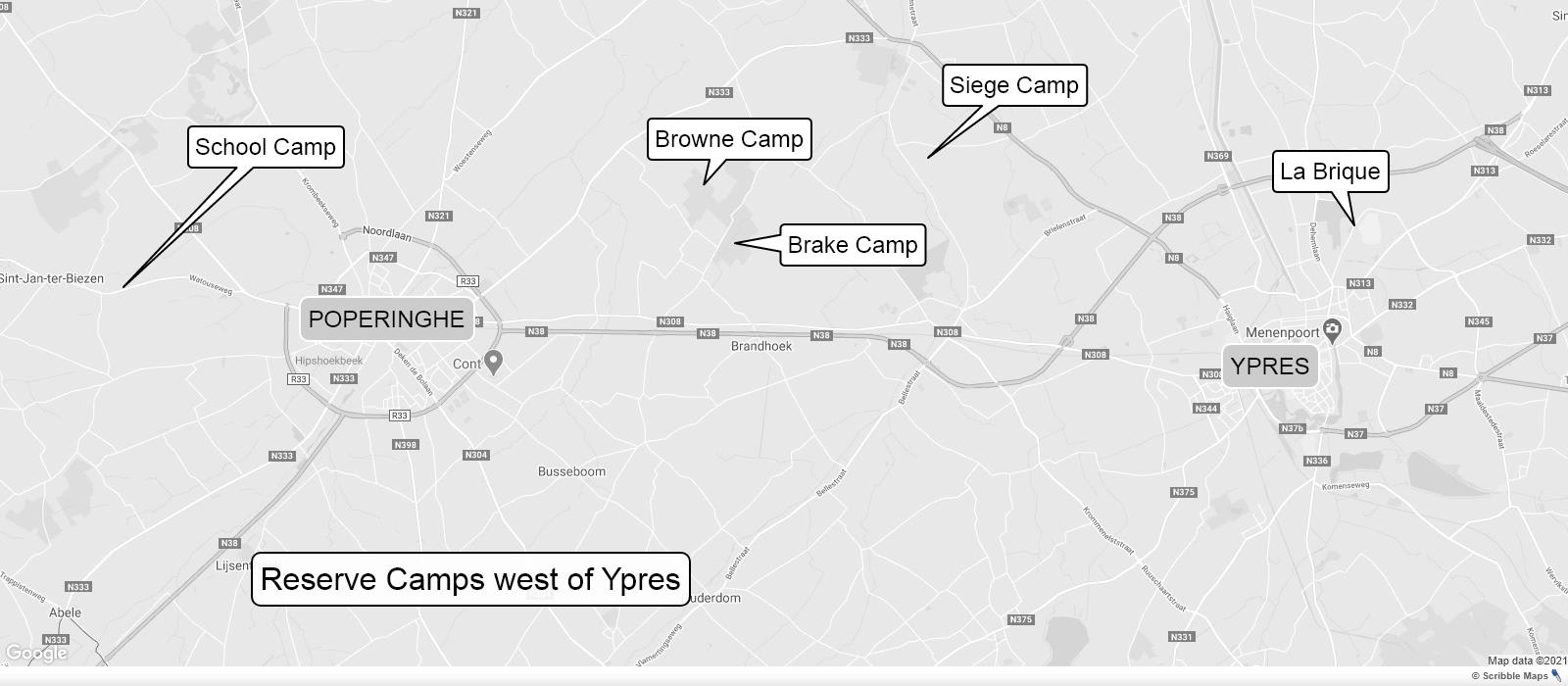

Map: Reserve camps west of Ypres

Poelcapelle - 3rd Battle of Ypres (October 1917)

During September the 1/7th continued training in the Dunkirk coastal areas, readying themselves for the start of a major offensive soon to start in the Ypres area. During the first week of October they moved into assembly positions west of Ypres. The Division had been ordered to take part in the offensive operations planned for 9th October 1917. On the 7th of the month the Battalion was in Vlamertinge Camp.

It bothered us that we knew we were to be in that mass attack and didn’t know any more than the Germans. We realised it would be a very tough job so all we had was to live in hope even if we die as the Jerries had too many machine guns for our liking.

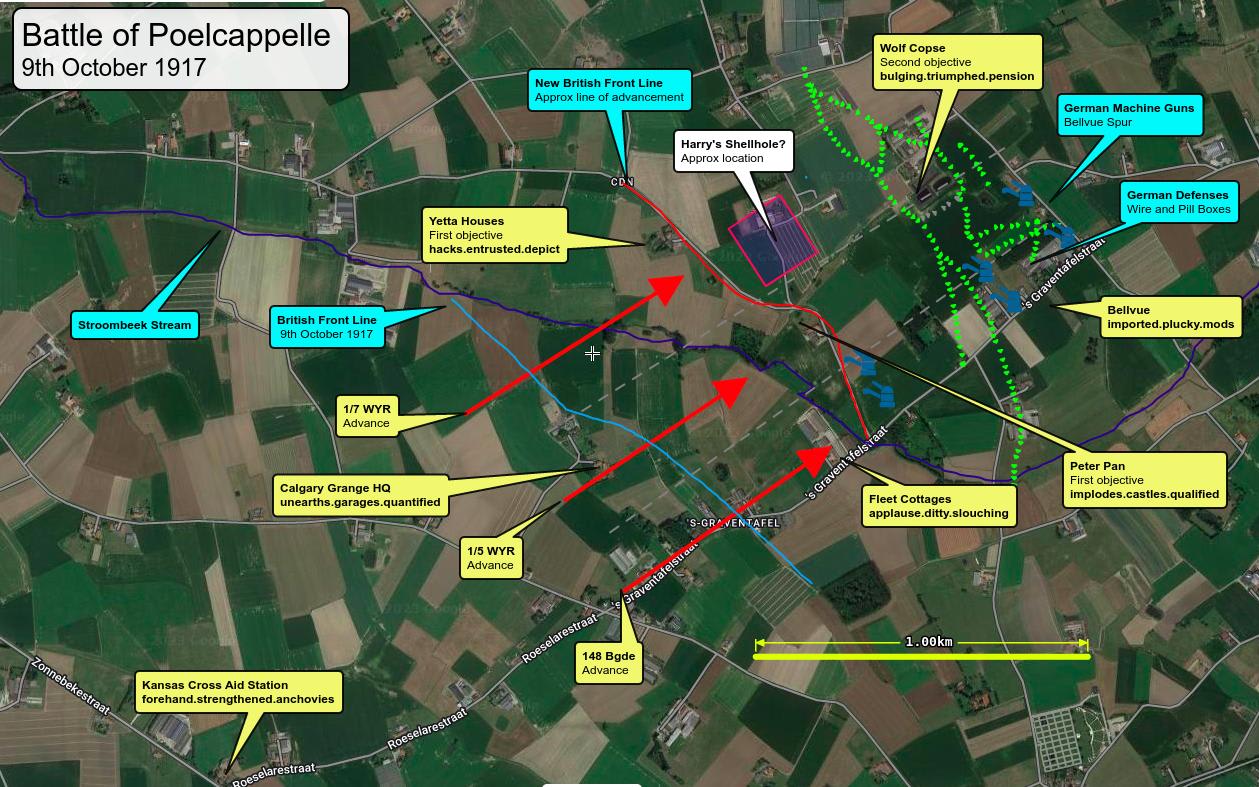

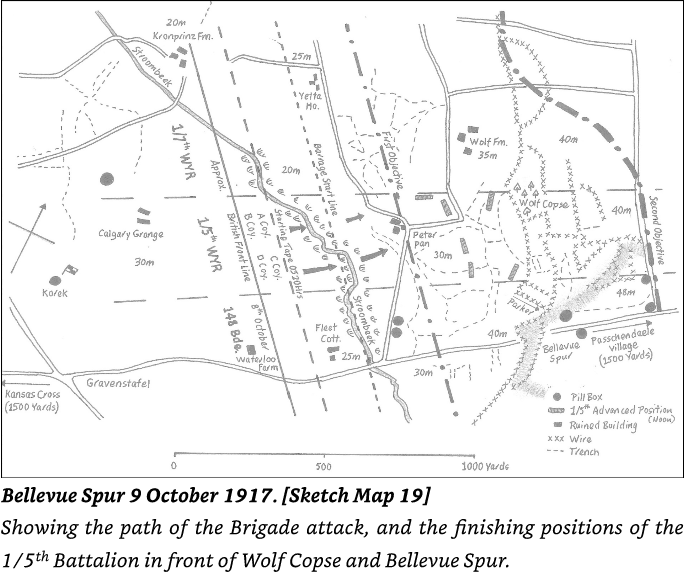

Aerial Map: Battle of Poelcapelle 9th October 1917

The 146th Brigade had been ordered to attack in conjunction with the 148th Brigade on the right and the 48th Division on the left. The attack was to be on a three-battalion frontage, i.e., 1/5th West Yorkshire’s on the right, 1/7th in the centre, and 1/8th on the left; the 1/6th Battalion was held in reserve. The objectives allotted to the three battalions were as follows:

1/5th Battalion West Yorkshire

- 1st Objective: Peter Pan

- 2nd Objective: Wolf Copse D.4.C.9.7.

1/6th Battalion West Yorkshire

- In reserve at Calgary Grange

1/7th Battalion West Yorkshire

- Ist Objective: D.3.d.9.4.

- 2nd Objective: Wolf Farm, D.4.C.3.8.

1/8th Battalion West Yorkshire

- Ist Objective: Yetta House D.4.a.0.4.

- 2nd Objective: D.3.d.3.7.

Map: Bellevue Spur

Colonel Tetley’s battalion (1/7th West Yorkshires) had reached their assembly position "dog tired", and when the barrage fell at 5-20 a.m., could hardly drag their weary bodies through the clinging mud and spongy morass which had to be passed before they reached their first objective. Moreover, the Stroombeek stream had to be crossed. It was not surprising, therefore, that the troops were unable to keep as close on the heels of the barrage as had been expected, though they made splendid efforts to do so. The heavy going and the objects to be crossed were responsible for a slight loss of direction, companies bearing off towards Peter Pan, but later this was remedied and Yetta Houses were passed at about proper distance.

In the Ypres Salient it was the custom when in the front line or support to ‘stand to’. That meant the everyone had to be ready in case of attack by the enemy. After a couple of hours we used to take turns to go into the dugout. Well, I stayed on watch until well into the afternoon.

I was amazed looking over the bulge of the Salient. It was just like one giant horseshoe and the destruction, well it was bad. In daylight the troops must have gone through hell in 1915 and 1916 defending Ypres. There was nothing standing, only stumps of trees. Looking back over the lake, I thought that anybody who gets out of this was will be very lucky.

A few nights later we were in semi darkness over very slippery, very muddy ground for such a long time. It was a case of 6 paces between each man. It was very difficult to walk between shell holes.

By what we could see in the darkness it was most horrible and we got to a duckboard track about a yard wide, but had to keep getting off due to shell fire. The track went in between two camouflaged field guns. Our guide had never told us about these. Both guns blasted off with a blinding flash and my foot went down on a broken piece of duckboard. I fell over into a hole well above the shins and slowly sank deeper. I was very lucky to go in feet first and also lucky that it happened by the edge. My pals were close by and one chap grabbed hold of the muzzle of my rifle and I hung onto the butt. I got out.

Some time later we reached a dugout. They had my puttees off in no time and then boots and stockings. I said there was a towel in my haversack. Gee I sure rubbed my feet and legs. Fortunately it was a warm wind. One of the chaps took my stockings out to dry. I put one foot in my cap comforter. He said "What are you going to do with the other foot?" Anyhow he lent me his.

Now when in the front line or support it was the custom to be all ready for action before daylight so I put my bare feet in my boots and was in the trench for hours until about one o’clock keeping a good lookout.

Battalion Headquarters had moved forward behind the attack and Colonel Tetley took up a position in shell-holes near Calgary Grange, where he awaited news of the attack. But it was about 7 a.m. before the first report reached him. At that hour a wounded officer — Lieut. Baldwin, O.C., Left Company — reached Battalion Headquarters and stated that his company was held up by machine-gun fire and snipers’ fire as soon as a move had begun from the line of the first objective. He had detailed two platoons to deal with the hostile machine-gun, but they had failed to silence it.

As no further information was obtainable, and no other reports were coming in from the front line, Colonel Tetley went up to near Yetta Houses and found his three companies consolidating with their left about 100 yards from Yetta Houses. The trenches were so crowded, however, that one company was collected and withdrawn to a line further in the rear. The front company (the Right Company for the first objective) was found near Peter Pan in touch on the right with the 1/5th West Yorkshires. The only officers (two) left on duty were with this company, all the officers and most of the senior N.C.O.’s of the front three companies having become casualties, hence the reason reliable information was difficult to obtain.

The 146th Brigade found a bridge on the Gravenstafel road and got forward several hundred yards up the Wallemolen spur beyond the Ravebeek, before being stopped at 9:30am, by the machine-guns in the Bellevue pillboxes and a field of uncut wire 25–40 yd (23–37m) wide in front of the pillboxes, which obstructed all of the divisional front. At about 1:00pm a reconnaissance report from a contact patrol aircraft crew had the 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division and 49th (West Riding) Division at the final objective.

Despite the scepticism of the brigade staff officers, both divisions were ordered to push forward reserves to consolidate the line. In ignorance of the cause of the check, the divisional HQ sent forward the 147th Brigade and the rest of the supporting battalions of the attacking brigades, which were either pinned down or held back on Gravenstafel spur, as the cause of the check was realised. In the afternoon the 148th and 146th brigades were near the red line, having had 2,500 casualties.

The 49th (West Riding) Division line began in the valley at Marsh Bottom, then along the bottom of the Bellevue slopes above the Ravebeek, to Peter Pan and Yetta Houses. Small groups were isolated further up the Bellevue slopes, on the western edge of Wolf Copse, Wolf Farm and a cemetery on the northern boundary.

There were about 50 of us and only room for a few. An officer yelled "Spread out and get in shell holes". They were all nearly full of water. Three of us were the very last to get in a shell hole and we must have been 80 yards from our nearest comrades.

Not only that, we were pinned down by gunfire. Even through the night and all next day they kept spraying bullets just above our heads.

The 1/7th Battalion had indeed suffered heavy casualties. The enemy’s machine-guns and snipers were cleverly hidden in concealed positions and were very active. They continued to fire through the barrage and entirely held up the advance to the second objective. A number of the enemy were, however, killed by Lewis-gun and rifle fire, the West Yorkshiremen taking every advantage of favourable targets. One brave fellow of the 1/7th (Rifleman C. A. Capp) rushed a hostile machine-gun single-handed. This gun had caused considerable loss and trouble. It was mounted on the parapet of a trench on the right, and the troops advancing on the left were caught in enfilade. As the gallant West Yorkshireman rushed the gun the German machine-gunners bolted, but as he could not work the gun he disabled it and rejoined his company. Capp, without doubt, saved the lives of many of his comrades, and was awarded the D.C.M. for his gallant exploits.

During the morning two companies of the 1/4th West Riding Regiment were sent up to Colonel Tetley, and at 2 p.m. he sent one company up to Yetta Houses to fill the gap between the left of the 1/7th and right of the 1/8th Battalions. Several small counterattacks on the 1/7th West Yorkshires were successfully beaten off and, on the night of 10th October, the battalion was relieved by New Zealand troops, the relief being carried out under heavy shell-fire from which many casualties were suffered.

You see, we did not know until the third day our division had been relieved and the third day I said to my two pals that I hadn’t heard any bullets. They agreed with me and the explosions did seem to be a long way off.

By that time not only were we exhausted but we found we could not stand. Anyhow we finally managed to get out. It sure was a struggle as our feet and legs were quite numb. We sure were miserable, wet and hungry and we got to the German Pill Box. Our legs and feet were dead. No wonder, as they had been in water most of the time we were laid in the mud.

One of them spotted a pill box about 50 yards away to our left. Then he saw some figures moving towards it. We shouted as loud as we could, one chap waved his hand. He came over and asked us what division we belonged to. We told him the 49th. He said it had been relieved over 24 hours ago. He was one of the New Zealanders from the Anzac Division and was taking four wounded and one blinded down to the nearest field hospital.

Somewhere about 5-30 a.m. on the 11th October, the New Zealanders completed the relief of the 146th Brigade, and all four battalions of the West Yorkshires were, by the evening, located in No. 2 Camp, Vlamertinghe.

Map: Bellevue Spur

The New Zealand Division found wounded of the 49th Division, "famished and untended on the battlefield.... Those that could not be brought back were dressed in the muddy shell holes. On the morning of the 12th many of these unfortunate men were still lying upon the battlefield, and not a few had meantime died of exposure in the wet and cold weather. Even before the attack, dressing stations and regimental aid posts as well as the battlefield itself were crowded with the wounded of the 49th Division.

In the meantime, Harry and his two pals then had a struggle to extract themselves from the battlefield and get to an aid station. His story continues ….

The Anzacs helped slide us through the mud and got us to the pill box. There was a pile of sandbags so we took off boots and puttees and put sandbags on each foot and two on each knee. We knew we would have a lot of crawling to do. The ambulance man of the Anzacs was marvellous. He said he would report our need for urgent help to an aid station.

Half an hour later we decided to try an extract ourselves. So off we went crawling. I could not keep up with my mates, they were stronger. They waited for me once but I told them to go on. I fell fast asleep. Setting off again I came to a spot I thought I recognised. In the distance I saw I was nearing a good solid road. Once on the road I stopped crawling and started rolling down the width of the road. It was far easier that way and I seemed to travel faster. After I had rolled onto my back about 50 times I sat up in the road and in the distance I could see Ypres. I hoped I could get to the trenches at the edge of Zillebeke Lake before it gets dark. I had my doubts about the road I was on. I thought it was the Warrington Road and on it previously was a pile of dead mules and horses. Fortunately they had been pushed to the side of the road. I did not waste any time there for obvious reasons.

The last two hours I was alone and scared to death as the big black ‘Heavies’ were busting in the sky. I was not very far at the side of one of the roads. That was like being under fire. The road had a sign on it that I remember quite clearly. Warrington Road.

I saw some men walking towards the road so I sat up and shouted. They came over to me. They were two officers and a padre. They asked me how I had got into that state. Then they found two men with a stretcher and they carried me to an aid station. I thanked them for their help and they hoped I would get to England.

Where did Harry crawl out to?

Harry constantly mentions Warrington Road, Hellfire Corner and Zillebeke Lake as his escape route to an aid station. But, these are not the closest, nor most logical aid stations to the battle.

Map: Harry's Crawl

The closest were at Kansas Cross and Spree Farm SW of the battleground and approximately 3km away from his shell hole. The Warrington Road area, however, is some 9km away south of Ypres. And, according to the War Diaries, the battalion had never been to the Warrington Road Sector up to the time of this incident. Yet Harry consistently refers to the Warrington Road in his recollections. We tend to believe Harry as the company did drift further to the south.

It is possible that Harry, confused, injured, tired and disoriented, just headed for the scarred blown out buildings that constituted the town of Ypres. Their ghostly outline would be unmistakable. But 9km is a long way to crawl, although he does say it took him hours.

Our view is that his own story is broadly correct, along with the implications for the route he took, although we are less sure about the accuracy of some of the specific details. I think there’s a good chance that he had wandered significantly further south than would at first sight seem logical for the following reasons:

1. The 1/7th advance may have drifted slightly southwards and Harry’s reaching a shell hole for cover may have pushed him further out of position

A ‘slight loss of direction’, with ‘companies bearing off towards Peter Pan’ was reported as they were initially getting into position.

The shell hole where Harry took cover was, according to his account, close to a Pill Box – according to the second map in your chapter (although admittedly it’s not very clear and may not be totally accurate) there are no Pill Box’s west of Wolf Farm or Peter Pan – it may be that the most likely are the pair positioned further south close to the ‘Gravenstrafel’ road (??), or others not marked.

Harry says they were the last to find a shell hole and they were some distance (80 yards) from their nearest comrades, which might also back up being somewhat ‘out on a limb.

2. He was spotted by an Anzac ambulance medic who guided them towards different aid stations (at Ypres, at Zillebeke Lake)

The aid stations at Kansas Cross and Spree Farm may not have been familiar to or used by the Anzacs.

The Anzac medic was in the process of taking Anzac wounded to an aid station when he came across Harry – in Harry’s other ramblings (i.e. amongst the 200+ other pages) he mentions that the Anzac medic said to them that he "was taking some wounded to a first aid station at Ypres and that they will send help to you"

That Harry and his 2 comrades followed the Anzac medic’s direction ("we had better get crawling back to Ypres") – possibly not in any sort of condition to challenge which aid station they were headed towards only relieved that they were being helped and guided to safety – would explain why they did not head towards Kansas Cross or Spree Farm.

From the 2 Pill Box’s close to the Gravenstrafel road it is approximately 9km (in a straight line) to both Ypres and to Zillebeke Lake which is broadly consistent with what the Anzac medic apparently told them about the distance involved.

3. He may have initially travelled further due south on being found by the Anzac medics

In another of his ramblings, he says that they asked the Anzac medic where they were at one point and were told that they were between "Zonnebeke and Broodseinde" – this is interesting and if anything like true then they were well south and very much in the area he describes.

If they had wandered this far south, either during or following the action (or even if this wasn’t totally accurate and they were actually slightly further north but not far from Zonnebeke/Broodseinde), then his coming across "a good solid road" can also be better explained as there are a number of possibilities – it could have been the tracks/roadways that now form the modern N37 and N332, or alternatively it could actually have been the Warrington Road or even possibly part of the Menin Road.

There is a general consistency in his repetition of this story – and we’ve heard it so many times now including directly from him on quite a few occasions! It’s always broadly the same although some of the details vary at times which isn’t surprising for an 80 year old recollecting events 60 years previously.

Geolocation References

- Calgary Grange 50.89452, 2.97932

- Wolf Copse 50.90146, 2.99204

- Peter Pan 50.89875, 2.98804

- Wolf Farm 50.90186, 2.98955

- Yetta Houses 50.9008, 2.98215

- Bellvue 50.89926, 2.99707

What 3 Words

Battlefield Maps

Hospitalisation and Recuperation (November 1917-April 1918)

Harry’s own words about his recuperation.

After I reached the aid station they transported me to a field ambulance and then into a large marquee and there I found my two shell hole mates. We were in that marquee for four days awaiting transport to take us well to the rear. I told a doctor what regiment I was with. He said "Do you live in Leeds?" He then asked me if I knew Doctor Fergus. I said "Yes, he’s our family doctor!"

Finally we got to a large hospital in Wimereux near Boulogne. I was well attended to by the doctors. What puzzled me was why my two mates were not in the same ward. Next morning I asked the sister. She told me that I was in a worse condition than them.

Two days later one of the nurses said to me "I guess you will be in England for Christmas, your knees to your thighs are terribly swollen and you are like a skeleton". The Doctor asked if I would like to go to England as a sitting case as I would be no use to the army for the next three months. I thanked him. After another 5 days, around the 156th or 16th December I boarded the hospital ship, St Patrick and arrived at Dover.

As I settled down on the train heading north I closed my eyes and prayed and hoped that never again would I be in the Ypres Salient. Having said that, I was really lucky as there were many thousands less fortunate.

We eventually got to a large hospital in Whalley, Lancashire. It was just 1 week before Christmas. I was asked if I would like to go to a convalescent home. I said yes.

Along with 19 others, mainly cockneys, we went to three houses in Colne, just outside Burnley. By gosh, it was really wonderful. Good food and attention, thanks to the cook and six nurses. I was the only Yorkshire chap. What a marvellous Christmas and New year we had.

At a pantomime one day a box of sweets was passed around from the back to the front. I turned around to thank them and sat directly behind me was Belle.

Note: Belle eventually became Harry’s wife and our Grandmother. In 1980 Harry wrote ...

Well on 15th March my dear wife passed away in Leeds Infirmary and I sure was broken hearted. I was like a pilot without a plane. We sure had a happy 56 years of happy married life, although it was very hard to make ends meet. But Belle never lost heart.

Funny thing is, if I would not have met her if I had not been in the Passchendaele area. I wouldn’t have had 56 years of happily married life with Belle.

I sure am very grateful that out of something very bad, something marvellous came to me and my family.

By the end of March 1918 I was marked fit and well and I must admit I was 100 percent better than I ever was. Two days later I was notified to report to Earsden (Alnwick) a few miles from Newcastle.

Just before I left Colne I met Belle outside the gate. I said to her, apart from sending a letter to my parents I do not write to anyone but if you give me your address I will send a letter to you.

Back to France (April 1918)

On 20th April 1918 Harry was back in France at St Martins Camp not far from Boulogne. This time he was posted to the 1st 5th of the 49th Brigade. Fortunately he arrived too late to be involved in the Battle of the Lys (Fourth Battle of Ypres) which was going on throughout that month, a major German offensive to cut off the Ypres Salient.

I arrived back in France on 20th April 1918. After spending the night in St Martins Camp a party of 100 of us arrived at a place named Obele. There were at least 100 of us and not a recruit amongst us. We had all been in the line before.

[Note: We believe this place to be Abeele, SW of Poperinghe]

An Officer asked me if I would like to be No1 Lewis Gunner. I said yes and for 10 days I was on a course. What’s more, I passed alright and my pay was 6d a day more. Out of the four gun teams I was the only one that hit the target, I suppose more by luck than judgement. We drove the instructors mad as we were only supposed to fire short bursts.

The next two weeks were pretty hectic. After 10 days I had passed all the tests. Next day he handed me a Webley revolver and two days later we were in support on the front line.

[This links with the next chapter when he is on the front line at Beauvoorde Wood, Abeele]

In 1917 and many times during 1918 I was asked if I wanted a stripe. I always said no, thank you. My excuse for that was that when you had authority to tell anyone to do something in the line, and they caught it, you are responsible for their death. That’s why I finished a full blown private, like I started.

Throughout May 1918, the flood of ‘new blood’ promised by General Cameron poured into the 1/5th battalion, with 17 officers and 592 other ranks joining. In June, July and August a further 9 officers and 326 Other Ranks arrived.

They had had more casualties in the last action. They sure had a lot of young chaps, quite a few from the south and quite a few from Manchester. Once more it was hard training.

While the reinforcement drafts received after the Somme and then Passchendaele had largely come from Yorkshire and northern England, in the summer of 1918 the 1/5th Battalion was brought up to fighting strength by an influx of recruits from all over Great Britain. Many were very young volunteers and conscripted men aged 18 and 19 who had been sent out hurriedly to replace the losses of the German Spring Offensive.

As Major General Cameron had hinted, the integration of so many barely trained men would be a challenge. Therefore, most of May and June was spent training in everything from basic musketry, with three days on the range at St Omer, to brigade attack schemes. Training was interspersed with the usual fatigues, as parties were sent out to help beef up the defensive fortifications between Poperinghe and Ypres. There was also an opportunity for rest and leisure activity as the usual impromptu and organised football matches started up on the beach.

From Etaples, Harry and his comrades travelled to the Poperinghe area. They were bound for the 1/5th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, B Company, which was at the time stationed in the line west of Ypres. He was aware that the 1/5th had been ‘wiped out’ during the recent German Offensive and that he and his friends were to ‘make up numbers’. The 1/5th Battalion was in the front line when he arrived but in reality this was a very quiet period.

Front Line, Kemmel Hill (May 1918)

Background

In April the Germans had made a big offensive (Operation Georgette) to break through to the coast and cut off the Ypres Salient. They were held back from their objectives by the Battle of the Lys, which was a series of battles at Messines, Hazebrook, Bailleul, Passchendaele, Kemmel Ridge & Sherpenberg. The British pulled troops from the Ypres Salient and reinforcements came in to fight against the new German front lines that had made inroads into their lines.

The final offensive in the Battle of the Lys came on 29th April. Seven German divisions advanced to the attack at 5.40am, on a sixteen kilometres front from Dranoutre to Zillebeke, after gas shelling and what one British division described as exceptionally heavy, large calibre, high explosive shellfire. Many reports comment upon the intensity of German activity in the air, with one British battalion complaining that as many as thirty planes were over our lines at one time, and none of our fighting planes were to be seen.

The objective of the attack was to reach the line Ypres - Vthmertinghe - Reninghelst - Westoutre - Mont Rouge. It was not remotely achieved, although mistaken French reports during the morning that enemy troops had reached Mont Rouge were most disconcerting until the actual situation became clearer.

Bavarian and Alpine Corps still held the left of the German front, and carried out the attack towards Locre, the Scherpenberg and La Clytte. Although a rapid advance was made, which reached Hyde Park, a position at the col between the Scherpenberg and Mont Rouge, the attack was badly affected by unexpected volumes of French artillery fire coming from the direction of Reninghelst. Machine gun and rifle fire also appears to have been more intense, steady and controlled than it had been four days previously. By the end of the day the German high command realised they could no longer achieve their objectives and called off the offensive.

The 1/5th had been decimated after the Battle of the Lys and sometime after 21st April, the 1/5th reinforcements, including Harry, were transported to the Abeele area, SW of Poperinghe and Proven. They were all experienced troops who had seen action before. The 1/5th had at this time yet to be reinforced by new, inexperienced troops from other parts of England.

One day during that first week of May 1918 Harry’s group of 30+ were left, leaderless, in a field on the front line looking south to the German lines. The following morning they were attacked by some 200 enemy troops, shells and bullets. At the end of the battle only Harry and his No2 Gunner remained. They escaped, the rest were either killed, wounded/captured or missing.

Firstly, let Harry tell his story.

Harry’s Story

We had to parade in battle order and we thought we were off for another four days in the line. We set off around 7pm walking and it was quite dark. What’s more we couldn’t see anything. I sure got a surprise when the officer took our platoon and gun teams into a field and told us to spread out and face the way he was. He said, Gunner Leak, take your team right to the end and we will see you in the morning. Get your oil sheets on the ground and rest.

What puzzled us was that there was not even a lance corporal with us. If only the Germans had known that we should have been taken prisoner quite easily without firing a shot. All of us were awake before it got light.

I expected them at 5am and they had not arrived at 7am. 15 minutes later 4 shells exploded 40 yards behind us. A short while after a load of Germans came out of a wood 400 yards away. There must have been 200 of them. If we had spent the night digging holes to fire from we would have stood a better chance. Thank goodness everyone in the platoon had seen service before in the front line. They knew to hold their fire until the Germans were much closer. Wasn’t long before we knew the situation was hopeless. Our chaps had done well, but they were outnumbered by about 10 to 1. First burst of fire from us and the Germans lost a number of men. We did not get off scot free as three of my team were killed, another badly wounded. My No2 said it looks like we are being prisoners.

We both scampered up the slope about 150 yards, dug a quick funk hole and set the Lewis Gun up. I have often thought that was the daftest thing I ever did as we only had 2 panniers of ammunition left (47 rounds).

It was a hopeless situation and I was watching the Germans put the wounded on stretchers. They certainly were busy, they also had casualties. Five of our chaps had their hands on their heads.

My No2 said there was someone creeping up on us through the grass. I said keep your eye on him. I was more concerned with the Germans at the foot of the slope. If they come up here I’ll take the cocking handle of the gun with me, but leave the gun so I can run faster.

[Note: And also, presumably, leave the Lewis Gun inoperable to the enemy?]

The person crawling to us through the grass was a British officer. He said those are Germans down there. I told him I was well aware of that. He replied, well fire. I said they are picking up the wounded. He replied, fire anyway. I was very abrupt, I said I will not, there were 30 of us down there and now there are only the two of us left. My No2 said fire a little burst to pacify him. I let a few rounds go towards the man on the moon, way above their heads.

Little did I know but by firing off that burst it nearly cost us our lives. We got back in the funk hole and were kneeling facing each other. A bullet from a sniper just whizzed past my right ear and if my mate had not had his gas mask on his chest he would have been a dead duck. He had his hands in front of his gas mask and it was really incredible. The bullet went between two of his fingers of his left hand and it just skinned the skin off. Did not smash a bone. He lost quite a lot of blood though. And that is God’s truth.

Right away we were off running to where that Officer had disappeared. About 50 yards away we met six or seven soldiers amongst the trees. I asked if they were 49th Division, they said no they were the 4th Division. They told us the 49th were over there about a mile to our right. In the darkness of the previous night we had been dumped in the wrong field. We sure were boiling mad that we had been left in that situation.

We crossed three roads before we got to see any of our lot, must have walked a mile and a half. The Sergeant said they had been looking for us all over. He asked me where have we been? I blew my top, told him he was full of tripe and almost got on a charge. I asked an officer why no one had come for us. Did they not hear any shell fire nor noise of any sort? We were dumped in that field and only two of us got out. Six or seven were taken prisoner and at least going on for 30 casualties. Some had paid the supreme sacrifice.

Seems we were put into the wrong field as we found out that we were in front of another Division on the blinking left.

I called them twerps! The Sergeant said he would have me up before the CO. I replied, I wish you would. He was from B Company and we were in A Company. Well, it was all hushed up. Next day we went back, I think it was, to Obey to get reinforced. That is where we got about 50 recruits, all young lads. Quite a few were from Kent and the London District. I got three in my gun team.

We left that spot and did not have any further contact with the Germans for quite a while. Soon after that we were back in the Ypres Salient up either side of the Menin Road, in trenches or down the other at the edge of Zillebeke Lake.

Initial Investigation

Harry had written about this incident many times. All of these recollections of the enemy action are consistent in his storytelling. But unfortunately, he never included place names, nor dates in his written notes. We had originally assumed (incorrectly) that it must have been referring to a time during the Pursuit to the Selle in October 1918.

Then we uncovered a series of notes with a similar storyline. This time, however, at the end, he mentioned that they were subsequently moved to the front line in the Ypres Salient near Zillebeke a few weeks later.

We originally assumed Harry wasn’t at the Battle of Lys in April 1918 as he was returning from convalescent leave in England. The 1/5th only went to the Ypres Salient in June through to August 1918 and never again during the war. That left the only possible date for this action was in May 1918.

We started looking closely at the 1/5th Battalion War Diaries for that month. The only time they were at the front line was between the 1st and 5th of the month. They had arrived from the Watou direction to the north. Their front line position was marked as a farm at map reference K23.b.0.6. Using trench maps from the time we found the farm. It was located NW of the village of Abeele, SW of Poperinghe and Proven. Right on the front line. This fits in with Harry’s incorrect naming of the place, ‘Obele’.

According to Harry, the action occurred near a wood. The only wood in the area is approx one to one and a half miles to the south west of the farm on high ground. This would have been the logical place to put troops looking out over the German lines further to the south and west. This fits in as in his recollections he mentions he had between a mile to a mile and a half to walk back to the Battalion.

Strange thing was, the Battalion War Diaries don’t mention any enemy activity whatsoever. But, there were casualties listed for the dates of the 4th, 5th and 7th of May. On those particular dates the battalion was either on Church Parade, Training, marching back to the reserve positions or at the reserve camp (School Camp). Not in any sort of action. Funnily enough, the amount of casualties listed in the War Diaries, totalled, would account for the troops missing from the Abeele skirmish.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission shows that 16 personnel from the 1/5th lost their lives between 1st and 3rd May. They are buried in various cemeteries throughout Belgium, France and England. Two have been ident

ge. 3. Why wasn’t the Company relieved as promised the next morning? 4. As the guns and shells opened up the next morning some one and a half miles away, why was support and help not forthcoming? 5. Who were the other troops they met in the woods? Harry says the 4th. 4th of what though?Breakthrough

A question put on the Great War Forum finally achieved the breakthrough and provided the missing link and uncovered the truth about what happened to Harry.

The following Battalion orders and messages help explain the tale and fill in the blanks in Harry’s story. Although rather long winded it makes for interesting reading.

146th Brigade War Diary Extract 27th April

146 Bde Composite Battn formed from the remains of Battalions (1/5 WYR, 1/6 WYR, 1/6WYR). Major R Clough 1/6WYR in command. 3 companies of 3 officers and 110 OR each. Total 15 off and 350 OR with necessary transport. Thus Battn became Divisional Reserve, 147th Brigade having a direct call on it.

1/5th Battalion War Diary Extract 28th April 1918

The Battalion consisting of 10 Officers and 66 OR moved by March en route to Hoograaf. 4 Officers and 120 O.R remained behind as part of a Composite Battalion under the command of Major R Clough and came tactically under orders of G.O.C 147th Infantry Brigade.

1/5th Battalion War Diary Extract 5th May 1918

In the evening the Composite Company consisting of 4 Officers and 98 O.R which had been attached to the 146th Brigade Composite Battalion rejoined the Battalion.

Probably unknown to Harry between 28th April and 5th May he (and his company) were reassigned to form a Composite Battalion of experienced troops that were much needed and then rushed to the front line to support the losses after the final days of the Battle of Lys.

Note that there are 22 O.R (Other Ranks) missing on their return on 5th May!

If we now turn our attention to the 147th Infantry Brigade we can examine their War Diaries to see what happened to Harry’s 146th Composite Battalion. Important parts are marked in bold. In total we have examined the diaries for:

- 147 Infantry Brigade

- 146 Infantry Brigade

- 1st 4th Duke of Wellington’s

- 1st 6th Duke of Wellington’s

- 1st 7th Duke of Wellington’s

- 7 Infantry Brigade

The following is in chronological order (as best we can make out):

147 Inf Brigade – Operation order No 164 30 April 1918

The 6th D of Ws will carry out this operation to connect up as stated with the 7th Inf Brigade on right at N.14.b.6.7 and the 7th D of Ws at N.9.c.2.2 on left. A line of posts should be established along this line and if the operation takes place this evening the posts will have time to thoroughly establish themselves. If, on the other hand, it does take place until tomorrow morning the posts should select inconspicuous positions and make what cover they can. I propose to hold the new line with the 146th Composite Battalion as soon as it is properly established and relief will probably be tomorrow night. The 5th Tank Battalion will not move until the new line is finally established and O.C 5th tank Battalion will prospect for new positions. This should be carried out with support companies leaving your old line intact until the new line is thoroughly established.

[N.B D of Ws = Duke of Wellington’s]

147 Inf Brigade – 30 April 1918

At 1:30am the 25th Division advanced their front line about 1000 yards on the right to connect up with the French, and the 6th Duke of Wellingtons threw out a line

of posts on their front to connect up. The French failed to advance, and the 25th Division and the 6th Duke of Wellingtons were bound to withdraw, the former having its right flank undefended. The morning was quiet but in the afternoon the artillery again became active. The Composite Battalion of the 146th Inf Brigade, strength 350, was placed at the disposal of the G.O.C 147th Inf Brigade. At 8pm, the 25th Division, in conjunction with the French, repeated operations as described above, and "C" Coy 6th Duke of Wellingtons, went forward to link up with the 25th Division and 7th Duke of Wellingtons. At Zero, on our barrage opening out, the enemy immediately put up his SOS signal and a terrific barrage came down on our front line, support line and back areas. The barrage lasted for 40 minutes. After bombardment had ceased "C" Coy 6th Duke of Wellingtons, pushed forward and took up the line, which had been given to them as an objective and established four strong posts on that line, touching up with 7th Duke of Wellingtons on the left flank. The 25th Division had suffered heavy casualties and were unable to establish their forward line, therefore the right flank of the 6th Duke of Wellingtons was unprotected. At about 12:15am on 1/5/18 "C" 6th Duke of Wellingtons was withdrawn and our original front line was held as before.147 Inf Brigade "Message & Signals" from 30 April 1918. Sent 2:45pm, received 7pm

1st May push forward to connect left of 7 Bde at N.14.b.6.7 to form own front line at about N.9.c.2.2 the strength of such advance being left to your discretion. On evening of 1st May under cover of darkness construct new front line from N.14.b.6.7 to N.15.b.0.6. It is expected that the above operation [unreadable] on the Battalion front. You may use Composite Battn of 146 either to conduct or hold the new front line or to relieve your own Battalion. Whatever you do you will have three Battalions under your hand for counter attack within out frontage from N.10.c.8.8 to junction with 25 Divn. Information just received that the time of above operation may be advanced to night fall tonight and a further operation take place tomorrow. Exact timings will be notified when found out.

1/4th Duke of Wellington Battalion – BM173 30 April 1918 10:15am

The 146 Composite Battalion will proceed to trenches in the area in the vicinity of N.1.b tomorrow and guides will be provided by 4th Duke of Wellingtons. 1 per platoon for the 3 Coys of the 146 Composite Battn and will lead them to trenches previously selected by O.C 4 D of W. Rendezvous for guides Rd Junction N.1.b.0.4 at 3:30am on morning May 1. Acknowledge.

1/6th Duke of Wellington Battalion – 30 April 1918 7:00pm

At 7pm particulars of operation to be carried out by 7th Brigade and French Divn were received with orders for Battn to establish line of posts from N.14.b.6.7 to N.9.c.2.2 to connect up with 7th Brigade on right and 7th Battn on left. Zero hour was 8pm and arrangements had to be hurriedly made. "C" Coy was detailed to carry out the operation with support platoon. This platoon moved forward at about 7:50pm. Barrage on 7th Bde and French fronts brought considerable retaliation but objective was reached with few casualties and line established. Touch could not however be made with troops on the right and it was found that although they had also reached their objectives the French troops had failed to get forward and troops of the 7th Brigade had been withdrawn. Orders were therefore issued at about 10:45pm to "C" Coy to withdraw to original position.

at H.31.c.2.01/4th Duke of Wellington Battalion – BM180 1 May 1918 3pm

One Coy Pioneers will be attached to 146th Composite Battalion tonight to make them up to 4 Coys. Reliefs as in BM177 will take place tonight 1 / 2 May. Relief of VERB by VEIN to be complete by 11pm. Relief of VEND by COMPO and Coy of Pioneers not to commence before 11pm. Dispositions of VEND on relief will be 2 Coys MILLEKRUISSE LINE, two Coys N.1.c.

1/6th Duke of Wellington Battalion – 1 May 1918

Day passed quietly. A good deal of movement was seen on Eastern slopes of KEMMEL HILL and it was thought the enemy was taking up assembly positions. The artillery dealt effectively with this.

1/4th Duke of Wellington Battalion – BM196 2 May 1918 11:25am

Warning order. The 147 Inf Bde and attached troops will be relieved on the 3 / 4 May by the 32nd French Division. Reconnoitring parties of six officers per battalion will reach Battn HQs, VEIN, 146 Composite Battn and VEND at about 2am 2 / 3 May where guides will be provided by above Battn. Further details of relief later.

1/6th Duke of Wellington Battalion – 2 May 1918

The Battalion was relieved on the front line by the 146 Composite Battn in early morning. Battalion on relief. "D" Coy to be in close support under orders of 146 Compo Battn

148th Infantry Brigade – 2 May 1918

The Brigade relieved 74th Infantry Brigade. Boundaries N.15.b.0.6 to N.10.c.7.2

1/4th Duke of Wellington Battalion – BM205 3 May 1918

The 3rd Battn is taking over the whole Bde front as follows

- (a) One Coy 3rd Battn from Coys of 146 Composite Battn in front line. Half Coy of 3rd Battn from Composite Coy in support.

- (b) One Coy 3rd Battn from Coys of VEIN & 5th Tank Battn in front line. Half Coy of 3rd Battn from Coys of VEIN & VEND support

- (c) The 1st Battn to relieve 6 D of W in support will be disposed as follows – 2 Coys 1st Battn in MILLEKRUISSE LINE. One Coy in trench in vicinity of N.1.d

- (d) No 2 Battn from 7 D of W in reserve

148th Infantry Brigade – 3 May 1918

The day was fairly quiet. From 3am to 6am enemy shelled N10 in bursts every 30 minutes and occasional shelling of N10 b and d. 146th Composite Battalion coming under command of 148th Infantry Brigade. At 8:35pm a heavy bombardment opened on right of Brigade.

1/6th Duke of Wellington Battalion – 3 May 1918

The day passed quietly – final orders were received for forthcoming relief by the French. At 8:30pm a heavy barrage was put down on front line, on roads and back areas. SOS was sent up on right and left – report received from front line Battalion stated that no attack had taken place. The situation had quietened by 10pm.

1/4th Duke of Wellington Battalion – War Diary Extract BA925 3 May 1918 11:10pm

Situation now normal on VEIN front. Enemy put down heavy barrage on front line, supports & Battn HQ but there was no sign of an infantry attack. SOS was not sent up from VEIN front line so far as I have been able to find out, it was sent up by a platoon of COMPO Battn on the right & by 148 Bde. Guides have been delayed as orders could not be got through owing to barrage.

147 Inf Brigade – 3 May 1918

3rd Battalion, 80th Regt relieved 4th Duke of Wellington’s Regt and Composite Battalion in front line trenches

148th Infantry Brigade – 4 May 1918

Very heavy artillery duel during the early hours of the morning. During the remainder of the day hostile artillery much below normal but fairly active at times in N.10.a and roads in N.4.c including a few gas shells. The Brigade (including 146th Composite Battalion) relieved in the line by 143rd French Rgt. On relief the Brigade proceeded to area G21.

148th Infantry Brigade – Message 6:00am – 4 May 1918

The situation is now quiet and the only shelling is by one enemy battery of 77mm. No enemy attack has developed as far as reports have been received. The SOS was fired on our front when it had been fired on both flanks

148th Infantry Brigade – Message 8:15am – 4 May 1918

SOS was sent up by Division on overnight

148th Infantry Brigade – Message 11:45am – 4 May 1918

MG fire very active from M.11.a. Enemy movement and sniping very slight.

148th Infantry Brigade – Message 2:45pm – 4 May 1918

Situation normal. 6am to 8:30am hostile artillery active on N.10.a and N.11.c. 10am to 2pm occasional shelling N.10.b and N.10.c.

147 Inf Brigade – 5 May 1918

The Composite Battalion was moved across to the left in reserve to the 148th

Inf Brigade and established Battalion HQ at Bloody Farm N.9.a.central taking over from the 9th Loyal North Lancs.148 Infantry Brigade – 5 May 1918

146th Composite Battalion rejoined their Brigade.

Map: Front Line Kemmel Hill 1st Week May 1918

Aerial Map: Front Line Kemmel Hill 1st Week May 1918

Questions and Answers?

This leads us yet again to the questions that Harry posed at the time. This time we might have some answers.

- Why was the Company put into a front line position overnight? Because the 146th Composite Battalion of experienced men were being used to extend the front line and link up between the 7th Brigade 25th Division on the right and the 7th Duke of Wellington’s on the left.

- Why was it leaderless? No ranking officer, no even a lance-corporal in charge. Possibly because of a lack of officers? Only 4 came into the 146th Composite Battalion from the 1/5th originally and if they were extending a line of posts then maybe they were needed elsewhere?

- Why wasn’t the Company relieved as promised the next morning? Possibly because the French and 25th Division weren’t able to extend their line and meet up with the right flank of the 146th Composite Battalion?

- As the guns and shells opened up next morning some one and a half miles away, why was support and help not forthcoming? There were reports of an SOS flare going up on the right flank that came from a platoon of the 146th Composite Battalion. Guides had been delayed as orders could not be got through owing to enemy barrage.

- Who were the other troops they met in the woods? Harry says the 4th. 4th of what though? The likelihood is that they were troops from the 1/4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. Another possibility is that the 25th Division on the right did include troops from the 1/4th South Staffordshire Regiment waiting to be relieved that evening.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Was it Harry’s SOS flare that was sent up? The times do not match. Harry suggests morning was the time of the attack yet Battalion records suggest early evening they saw flares and had an enemy barrage. So possibly not.

The 146th Composite Battalion seems to have been passed around a bit between Battalions for those few days in May (see numerous mentions in War Diary Extracts). It was also a time of great confusion and uncertainty. The French army was also moving into the area and starting to relieve the British. Nobody will ever know really how this all came about but it does seem likely that Harry’s platoon were on the far outer reaches (right hand side) of the new line of front line posts that the 147th wished to establish. On a dark night it would have been easy to push out the line too far and isolate the platoon quite a long way from the main front line.

If indeed Harry’s platoon was isolated in a field to the far right of the rest of the 146th Composite Battalion, then they could easily have come under attack from German forces in the lower woods of Kemmel Hill (The "Kemmelberg").

The shaded area on the map above shows the likely area where this occurred. But it is all speculation at this stage. The battlefield should really be visited to try to pinpoint Harry’s memories with the actual lie of the land and see if there are any similarities.

Trench Maps

Geolocation References

Geolocation

- N.14.b.6.7 (146th - right flank) 50.7965, 2.81843

- N.9.c.2.2 (146th - left flank) 50.79904, 2.82262

- N.15.b.0.6 (146th – new line left flank) 50.79603, 2.82849

Google Maps

What 3 Words

Ypres Summer Reinforcement (May-August 1918)

During the next two weeks it was always the same routine. Then we moved to the Pop front to hold the line. We would spend time in the line and then time in support.

["Pop" was the soldiers slang for the town Poperinghe, west of Ypres]

A few days later we were back in the Salient up towards Zonnebeke, Kemmel, Dickebusch on one side of the Menin Road or up towards Langemark on the other. Most of the time we were in the Zillebeke trenches and we sure got used to that area. I saw that track many times in the next couple of months without further trouble.

I was sure surprised looking in the direction of Zonnebeke. The bulge was so small compared to what it had been in 1917. There must have been some bitter fighting and the German attack certainly got close to Ypres.

Map: Ypres Front Summer 1918. Marked are Hellfire Corner, Dilly Farm, Potijze & Zillebeke Lake

Location Extracts from 1/5th War Diaries

June 1918

- 1st to 3rd June Camp Proven area F1.c.6.2

- 4th - 11th Siege Camp Divisional reserve

- 12th - 17th Left sector, right sub-sector. Thatch Barn, Dilly Farm, Boundary Farm

- 18th - 22nd Ypres I8.b.30.85 Brigade Reserve KAAIE Defences

- 23rd - 29th Left sector, right sub-sector

- 30th Divisional reserve, Brake Camp

July 1918

- 1st - 7th Divisional Reserve Brake Camp

- 8th - 23rd Left sub-sector, right brigade. Menin Road, Hellfire Corner, Mole Track, Rifle Farm, Gordon House, West Farm, Goldfish Chateau

- 24th - 30th Siege Camp in reserve

- 31st - Reserve Battalion, left sector. Suicide Corner, KAAIE defences, Dead End

August 1918

- 1st - 8th Reserve Battalion, left sector. Suicide Corner, KAAIE defences, Dead End, Lille Gate Baths

- 9th - 16th Left sub sector, right brigade. Mill Cot, Crump Farm, Market farm, Cambridge Road

- 17th - 18th Siege Camp, reserve Brigade

- 19th Pigeon Camp, Proven

- 20th - 22nd Herzeele

- 23rd Nortkerque

- 24th - 28th Tournehem

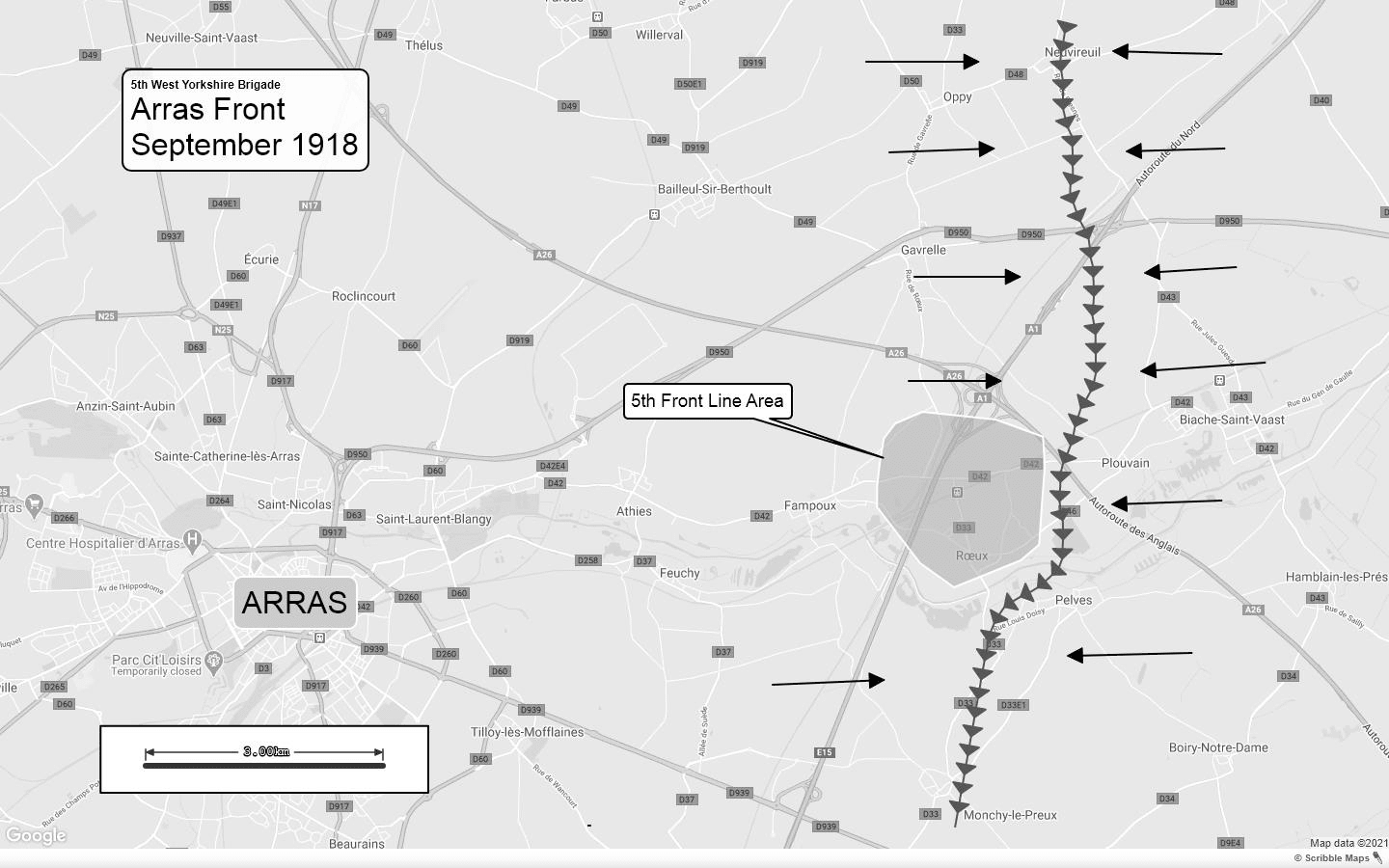

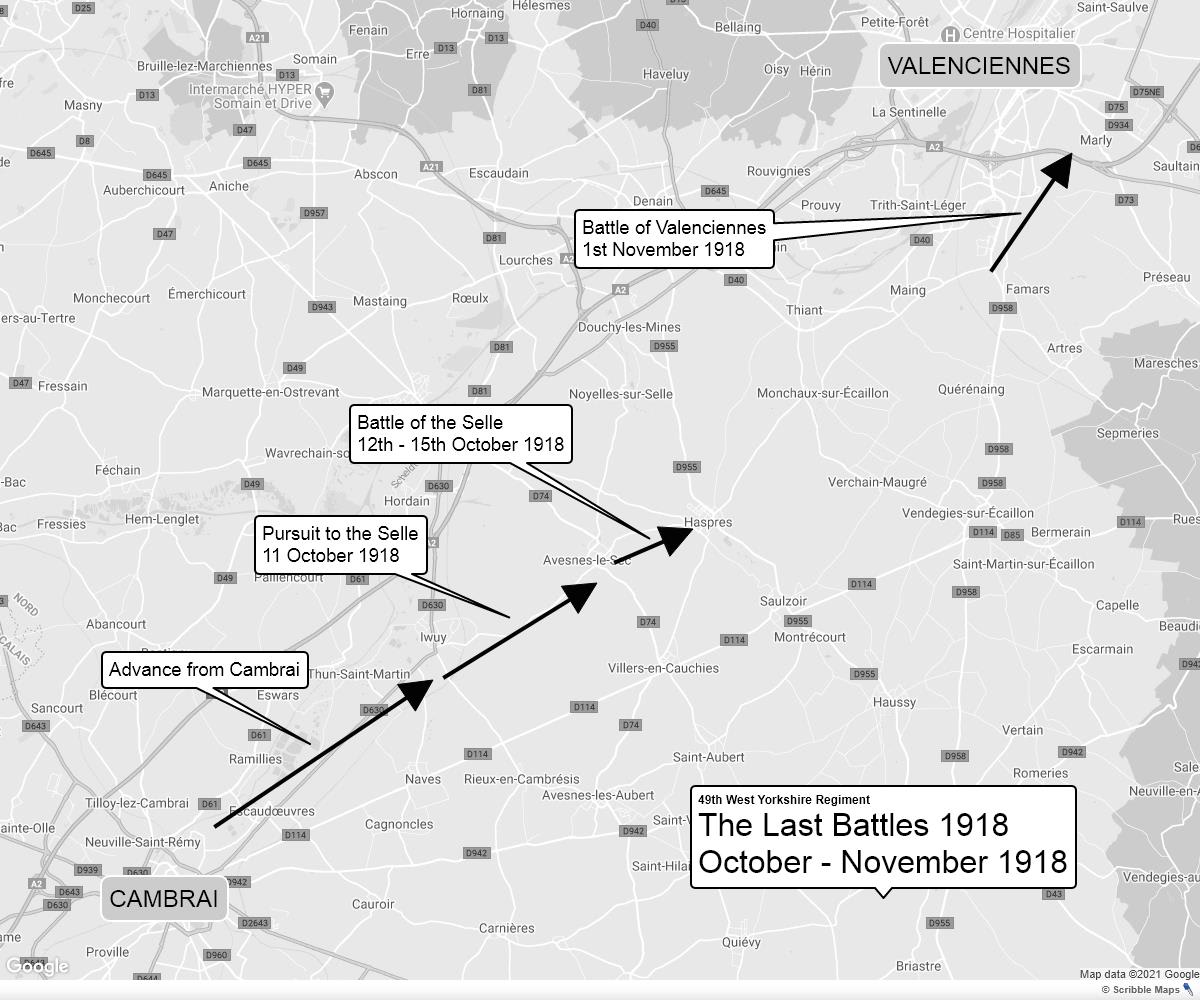

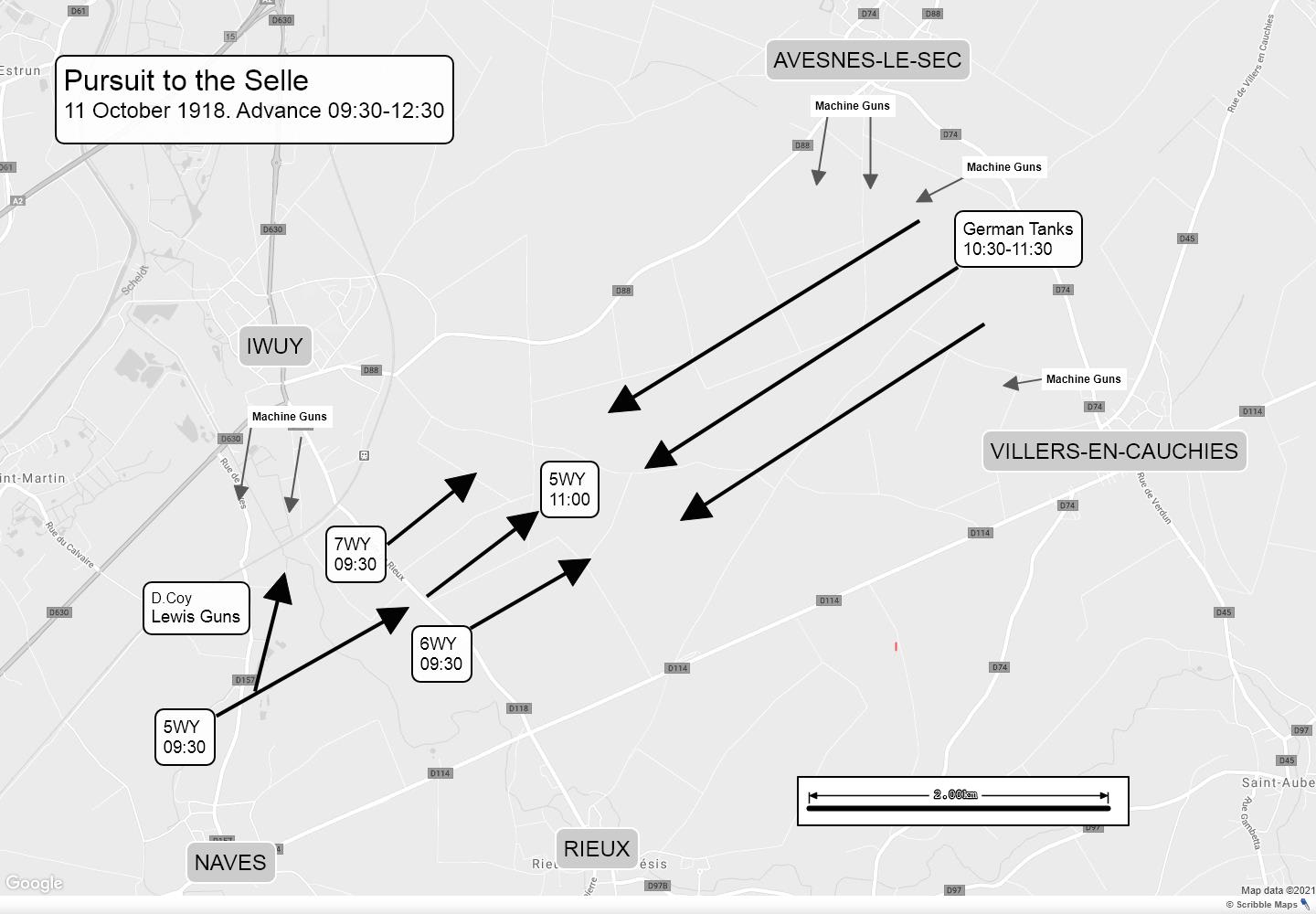

- 29th - 30th Foufflin-Ricametz